A Hamlet on the Ganges, or a Poetics of Psychoanalysis

From the Field of Indian Linguistics to the Function of Analytic Discourse

Author’s Note: Given the length of this essay, I’ve made a PDF available for those who wish to print and read on paper:

Preface: An Aesthetics of Analysis

The omnipresence of human discourse will perhaps one day be embraced under the open sky of an omnicommunication of its text.

—Jacques Lacan, Écrits

Is the unconscious an amorphous mass of thoughts, of signifiers sliding above what is signified? Or is the current of discourse an aesthetic mood, an aromatic affect that tastes its own speech in the crafting of syllables? If the unconscious is structured like a language, then the edifice of its hand and foot is a metered lyric, a loose thread that spins an architecture of being, a rhetorical anatomy of lyrical flow.

In India, the field of linguistics (along with its associated disciplines of grammar and poetics) has been placed in the category of “aesthetics” since antiquity. Long before the Freudian discovery of the unconscious, Indian sages elaborated the literary structure of the human psyche and the structural nature of language. The Rig Veda, for example, is one of the oldest surviving written texts and is composed entirely in metrical verse. This is because Indian aestheticians revered poetry as the highest form of art, and thus cast their philosophical and spiritual treatises in poetic forms.

In Sanskrit, the study of linguistics and grammar is referred to as vyākarana,1 a term that means “analysis”, “explanation”, “prediction”, and “the sound of a bow-string”. The prefix vyā means “analysis” and kārana means “to effectuate”. Thus, vyākarana is the process of analysis. Vyākarana is also consonant with vāk (“speech”) and vākya (utterance). Here, the Sanskrit signifier has already laid bare the very meaning of psychoanalysis and language: an enigmantic art of discourse that divines an oracular speech, or what we may declare an “analytic discourse”.

A similar meaning is discovered in the Sanskrit term, upanishad. “Upa” means “near”, “ni” means “down”, and “sad” means “to sit”. Thus, Upanishad is commonly translated as “to sit near [a master]”, suggesting a primal circumstance of oral transmission where the disciple hears and receives the teachings from a master, typically in a forested setting. However, the eighth-century sage, Shankara, derives the meaning of upanishad from the substantive sad, meaning “to loosen”. According to Radhakrishnan, “If this derivation is accepted, upanisad means brahma-knowledge by which ignorance is loosened or destroyed”.2 This is an acceptable rendering given the philosophical context of the Upanishads. Yet, I wish to take Shankara’s derivation further, in order to point out the semantic resonance between upanishad and analysis.

The English term analysis is derived from the Greek analuein, meaning “to loosen”. If analysis and upanishad render the connotations of “loosening” in two distinct tongues, then the linguistic link between psychoanalysis and Upanishadic thought is already tied together. The influence of Upanishadic Advaitism on Greek philosophy is an anthropological inquiry we will leave aside, except to note that scholars have posited the influence of the Upanishads on Plato, Socrates, and Pythagoras. In addition to their philosophical similarities, the Indians and Greeks both employ a dialectical method of discourse as a format of philosophical inquiry, a structure which the Upanishads are an early example of. The discourse of the Upanishads is thus an analytic discourse—in its structure and its pedagogy.

What is analytic discourse? In Seminar XIX, Lacan asks, “What is the function of speech? The discourse of the analyst is formed in such a way as to make this question emerge. The function and field of speech and language—that’s how I introduced what would lead us to the present point of defining a new discourse”.3 Lacan is referring to his topological paradigm of the four discourses, a quadration that begins with the “discourse of the master” and concludes with the “discourse of the analyst”. Lacan continues to introduce his notion of analytic discourse by citing linguistics:

To introduce what is involved in the analytic discourse, I had no qualms about helping myself . . . to the facilitation provided by what is called linguistics. To quell the ardour that might have been too quickly aroused in my vicinity . . . I reminded you that this something that is worthy of the title linguistics as a science, which seems to have language and even speech as its object, was supposed only on the condition that the linguists swear amongst themselves never—or never again, because this is what people had been doing for centuries—even remotely, to allude to the origin of language. This was one, among others, of the watchwords I gave to the form of introduction that was articulated in my formula the unconscious is structured like a language.

. . . On no account is it a matter of speculating about any origin of language. I said that it’s a question of formulating the function of speech.4

Months before he delivered his essay, “The Function and Field of Speech and Language in Psychoanalysis” in Rome, Lacan gave a prefatory talk titled, “The Symbolic, the Imaginary, and the Real”. Here, speaking to the existence rather than the origins of language, Lacan says, “Language exists. It is something that has emerged, we shall never know either when or how it began, or how things were before it came into being”.5

Lacan is clear that the question at hand is not one of historical or evolutionary linguistics. Rather, the question is a structural inquiry into the function of speech, which he regards “to be the only form of action that posits itself as truth”.6 Speech functions as truth because of its autonomous activity—“Not only do I speak, do you speak, and even ça parle, it speaks, as I said, but this carries on all by itself . . . A word that founds a fact is a fact of saying, but speech functions even when it doesn’t found any fact. When it gives a command, when it prays, when it insults, or when it voices a wish, it doesn’t found any fact”.7

In other words, the function of speech is the truth of its enunciation, of its incarnation in the letter that speaks in revolutionary tongues. It is from here that Lacan continues his discussion with references to Plato, the Stoics, and Saussure, asking, “Where does meaning arise? It is in this respect that it’s very important to have made the division . . . that Saussure made between the signifier and the signified . . . Moreover, this was something Saussure inherited from the Stoics . . .”.8 To complete Lacan’s thought, I will suppose that this was something the Stoics inherited from the Indians.

Indeed, Lacan ultimately concludes that the question of meaning is an enigmatic riddle (the likes of which we will soon encounter in the poetic verses of the Rig Veda): “When all is said and done, this meaning is an enigmatic riddle, and it’s an enigmatic riddle precisely because it is meaning”.9

In his introduction to The Principal Upanisads, Radhakrishnan positions the Vedic concept of speech (vāk) as analogous to the Greek logos. He writes:

For Plato, the Logos was an archetypal idea. For the Stoics, it is the principle of reason which quickens and informs matter. Philo speaks of the Logos as the ‘first born son’, ‘archetypal man’, ‘image of God’, ‘through whom the world was created’. Logos, the Reason, ‘the Word was in the beginning and the Word became flesh’. The Greek term, Logos, means both Reason and Word. The latter indicates an act of divine will. Word is the active expression of character. The difference between the conception of Divine Intelligence or Reason and the Word of God is that the latter represents the will of the Supreme. Vāc is Brahman. Vāc, word, wisdom, is treated in the Rig Veda as the all-knowing. The first-born of Rta is Vāc: yāvad brahma tisthati tāvatī vāk. The Logos is conceived as personal like Hiranya-garbha. ‘The Light was the light of men’. ‘The Logos became flesh’.10

Hiranyagarbha means “golden womb” and refers to the primeval source of the universe. In the Rig Veda, hiranyagarbha is associated with the deity Prajāpati, the lord of all creation. In the Yajur Veda, Prajāpati self-emerges from Brahman and co-creates the world with Vāc, the lord of speech. (In section III, we will return to Prajāpati’s prominence in the Upanishads, as the one whose utterance bestows the gift of speech).

The Vedas and Upanishads thus pose the function of speech as the process of incarnation, a scriptless verse of vowels and consonants, a speaking body become avatar in enunciation. Thus, in Indian thought, speech is seen as the intersection of psyche and soma, where the breath of life makes itself known in free associations.

This brings us to the foot upon which the speaking body of this essay has erected its structure: the radical essay, “The Function and Field of Speech and Language in Psychoanalysis”, where Lacan articulates a poetics of psychoanalysis. Lacan accomplishes this noble task not only by returning to Freud but by tracing the field of the unconscious to its roots in Indian poetics. My task in this essay is to trace the links between Indian linguistics and Lacanian psychoanalysis, so as to map the aesthetic topography of the psychoanalytic art as an East-West dialectic, not only to return to a past but to chart a future of its practice.

My approach revolves around a close and chronological reading of Lacan’s “Function and Field”:

In section I (From Sanskrit to the Signifier), I trace the influence of Indian grammarians on Ferdinand de Saussure and the eventual influence of Saussure on Lacan’s conception of psychoanalysis. I introduce Lacan’s notion of the “field of language” and the “function of speech” as operative in the unconscious and in the analytic frame.

In section II (The Gift of Speech, or the Prosody of Prasad), I focus on Lacan’s references to Indian linguistics via Abhinavagupta and the concepts of dhvani and laksanalaksanā. I add essential context to Lacan’s discussion by quoting from a text on Indian aesthetics that he references.

This commentary culminates in section III (What the Thunder Spoke), where I place the convergence of Indian poetics and European psychoanalysis in Lacan’s concluding reference to the Upanishads.

My writing mirrors my practice—I punctuate threads of association with lucid intervals of interpretation. For if psychoanalysis offers us anything, it must be the realization of an inimitable style of symptom. If anything, I hope that I have not only illustrated the influence of Indian linguistics on Lacan’s psychoanalytic theory but have also crafted a key that unlocks an aesthetic force in the navel of the unconscious—a rasa that colors and tones the speaking body with its gifts.

I. From Sanskrit to the Signifier

Rigvedic poets glory in their grammar and are skillful in exploiting not only the many distinctions it provides but also grammatical ambiguities and neutralizations of grammatical distinctions. Moreover, since basic information, such as the identity of the grammatical subject and object, is coded on the word, the poet is free to use word order for rhetorical purposes, placing particularly significant words in emphatic positions such as initial in the verse line.

—Stephanie Jamison & Joel Brereton, Introduction to The Rigveda

A witness blamed for the subject’s sincerity, trustee of the record of his discourse, reference attesting to its accuracy, guarantor of its honesty, keeper of its testament, scrivener of its codicils, the analyst is something of a scribe.

—Jacques Lacan, Écrits

In 1953, Lacan delivered one of his most seminal discourses to the Rome Congress at the University of Rome—“The Function and Field of Speech and Language in Psychoanalysis”. Also known as the “Rome Discourse”, this essay was first published in Lacan’s Écrits in 1966.

As an essay, “Function and Field” is a remarkable written text—not only substantial but literary, oratory, and even oracular. Lacan illustrates the function and field of speech and language in his own rhetoric, as he declares in the Preface, “If, then, my talk was to be nothing more than a newborn’s cry, at least it would seize the auspicious moment to revamp the foundations our discipline derives from language”.11

Lacan’s title is a parallel structure—the function of speech and the field of language. As he says in the Introduction, “My task shall be to demonstrate that these concepts take on their full meaning only when oriented in a field of language and ordered in relation to the function of speech”.12 For Lacan, the field of language extends into the very roots of Proto-Indo-European—the Sanskrit language. On this basis, Lacan articulates the function of speech as a discourse of poetics, especially the poetics of Abhinavagupta.13 In the course of the essay, Lacan ties the knots of Indian poetics and his psychoanalysis by citing the linguistic concept of dhvani to illustrate the function of speech. But the link between Indian linguistics and Lacanian psychoanalysis was first transferred in the influence of Ferdinand de Saussure on the core of Lacan’s teaching—that “the unconscious is structured like a language”.

Saussure taught Sanskrit and Indo-European languages at the University of Geneva. He was significantly influenced by Indian linguistics, especially Pānini,14 the “father of linguistics”, whose Astādhyāyī had reached European scholars in the early nineteenth century. Saussure’s interest in Sanskrit was foundational to the development of his linguistic theory, a fact that is especially evident in his earlier works—Memoir on the Primitive System of Vowels in Indo-European Languages (1878) and his doctoral thesis, On the Use of Genitive Absolute in Sanskrit (1881). According to Ananta Shukla, who translated Saussure’s thesis into English, Saussure

did not simply take up the subject [of Sanskrit] at random; but worked on this topic deliberately as it taught him two foundational aspects of his general linguistics (1) the synchronic system of language (that is actually spoken) is a system of relations (sambandha) and (2) it is use rather than any imposition of preconceived system of rules that constitutes a language either living or dead.15

In “The Function and Field”, Lacan implies a connection between Indian linguistics and European psychoanalysis as the core thread woven in a poetics of psychoanalysis. As Saussure asks, “But what is language? It is not to be confused with human speech, of which it is only a definite part, though certainly an essential one. It is both a social product of the faculty of speech and a collection of necessary conventions that have been adopted by a social body to permit individuals to exercise that faculty”.16

We already hear the echoes of Lacan’s structural distinction between language and speech: language exists in a field of signifiers, speech exists as the function of enunciation. Lacan thus opens the first section of the essay by saying, “Whether it wishes to be an agent of healing, training, or sounding the depths, psychoanalysis has but one medium: the patient’s speech”.17 In putting this remark forward, Lacan establishes the relevant ground of his exploration, that psychoanalysis is not only concerned with speech but with the function of speech.

The patient free associates and thus enunciates a transcript of their unconscious scripture, to which the analyst functions as a scribe who transcribes and punctuates the spoken word. Here, the analyst is less concerned with what the patient says as the fact that the patient says it. As Lacan elucidates, “. . . Speech, even when almost completely worn out, retains its value as a tessera. Even if it communicates nothing, discourse represents the existence of communication; even if it denies the obvious, it affirms that speech constitutes truth; even if it is destined to deceive, it relies on faith in testimony”.18 The analytic art is thus not a symbolic interpretation but a carefully placed mark in the grammar of the real, for “it is . . . a propitious punctuation that gives meaning to the subject’s discourse”.19

Speech as tessera is speech as word-fragments in an obscured mosaic of meaning. A tessera is a portion of the real, a phonetic fragment that enunciates in the gift of speech, whether it knows yet what it says. This leads Lacan to his famous admonition to a young psychoanalyst, “Do crossword puzzles”, placed as an epigraph to the second section of his essay.

In section two, Lacan continues to develop the textual implications of speech. Lacan returns to Freud’s comment that the “dream is a rebus”, which he interprets to mean that “a dream has the structure of a sentence or, rather, to keep to the letter of the work, of a rebus—that is, of a form of writing, of which children’s dreams are supposed to represent the primordial ideography, and which reproduces, in adults’ dreams, the simultaneously phonetic and symbolic use of signifying elements found in the hieroglyphs of ancient Egypt and in the characters still used in China”.20 Lacan’s reference to hieroglyphs is notable, as twenty pages later he compares Freud to Champollion, the French philologist who famously deciphered Egyptian hieroglyphs. Here, Lacan is emphasizing the nature of the dream as a coded message, but a message that is nonetheless written even in its delivery. For “what is important is the version of the text”, Lacan declares, “and that, Freud tells us, is given in the telling of the dream—that is, in its rhetoric”.21

“Rhetoric” is the art of speaking and writing that makes use of compositional or stylistic techniques. Lacan follows his remark with a list of the rhetorical devices that the analyst must listen for: “Ellipsis and pleonasm, hyperbaton or syllepsis, regression, repetition, apposition—these are the syntactical displacements; metaphor, catachresis, antonomasia, allegory, metonymy, and synecdoche—these are the semantic condensations . . .”.22 Lacan’s list includes a combination of grammatical, orthographic, and poetic techniques, the reading of which he proposes as the basis of analytic interpretation.

Analytic listening thus requires a sensitivity to the poetics of speech—its puzzling and enigmatic nature. This esoteric mode of rhetoric is well-established in the riddling hymns of the Vedas, the puzzling inquiries of the Upanishads, and the paradoxical utterances of Zen koans. The register of poetic discourse is spoken with an esoteric intent, or concealed meaning, that differs from the exoteric intent, or obvious meaning, of everyday speech. Commenting on the poetic rhetoric of the Rig Veda, Jamison and Brereton explain that

[m]uch of the Rigveda is enigmatic, not only because of our distance from the time of its creation, but also because the poets meant it to be enigmatic. They valued knowledge, especially the knowledge of the hidden connections . . . between the visible world, the divine world, and the realm of ritual. They embedded that knowledge in hymns that were stylistically tight and elliptical, expressively oblique, and lexically resonant.23

Lacan’s emphasis on poetic rhetoric is innovative. His attention for the patient’s speech is rooted in Freud’s observations, but Lacan articulates this insight with an incisive clarity on the relationship between speech, language, and symptom:

. . . [I]f [Freud] teaches us to follow the ascending ramification of the symbolic lineage in the text of the patient’s free associations, in order to detect the nodal points of its structure at the places where its verbal forms intersect, then it is already quite clear that symptoms can be entirely resolved in an analysis of language, because a symptom is itself structured like a language: a symptom is language from which speech must be delivered.24

Speech is given an elevated power, bearing the function of deliverance from the symptomatic syntax in which language has been ciphered. Since the symptom is structured like a language, speech has a curative diction. Lacan ultimately develops this emphasis as the “gift of speech”, a notion we can trace to the Vedic and Vedāntic understanding of speech.

II. The Free Gift of Speech, or the Prosody of Prasad

Suggestion can neither have fixed rules of grammar or the rigid definition of the lexicon so easily available to the scholar. Suggestion has its unanalysable code which finds its depth of explanation in the living hearts of the people who use it.

—Rabindranath Tagore, Foreword to The Philosophy of the Upanisads

Is it with these gifts, or with the passwords that give them their salutary nonmeaning, that language begins along with law?

—Jacques Lacan, Écrits

Lacan initiates his argument with a reference to the Yijing:

Through the word—which is already a presence made of absence—absence itself comes to be named in an original moment . . . . And from this articulated couple of presence and absence—also sufficiently constituted by the drawing in the sand of a simple line and broken line of the koua [gua] mantics of China—a language’s world of meaning is born, in which the world of things will situate itself.25

The solid and broken lines referred to here are the six lines that compose one of the sixty-four hexagrams of the Yijing, or Book of Changes. The solid line represents the yang principle, the broken line represents the yin principle. In Daoism, it is the ceaseless alternation of yin and yang that is said to give birth to the ten thousand things. Or, as Lacan says, “It is the world of words that creates the world of things”.26

Lacan also draws on the Greek concept of logos—he places the Word as the creative origin of the world and thus bestows upon speech its primordial function. This leads directly to Lacan’s articulation of the “name of the father” as the dawn of the signifier of the symbolic pact in which language derives its law. He comments on Levi-Strauss’s notion of the elementary structures of kinship to further ground the relation between the name of the father and the symbolic register of language and social communication: “Isn’t it striking that Lévi-Strauss—in suggesting in myths of language structures and of those social laws that regulate marriage ties and kinship—is already conquering the very terrain in which Freud situations the unconscious?”27 Speech thus becomes the very basis for psychoanalysis, since it holds within its Oedipal tongue the matrimonial ties of paternity and maternity. Therefore, Lacan holds that psychoanalysis must concern itself with poetics.

Lacan now ties the thread of poetics and psychoanalysis with pedagogical intent. After noting the “list of disciplines Freud considered important sister sciences for an ideal Department of Psychoanalysis”,28 Lacan proposes the addition of “rhetoric, dialectic . . . grammar, and poetics—the supreme pinnacle of the aesthetics of language—which would include the neglected technique of witticisms”.29

Now, we come to the third section of Lacan’s opus, where he makes the first direct reference to Indian linguistics. Lacan is discussing what he calls “primary language”, that is the language of the subject’s desire, which “he is already speaking to us unbeknown to himself . . . in the symbols of his symptoms”.30 It is these symbols in the symptom that analytic technique evokes “in a calculated fashion in the semantic resonances of his remarks”.31 This amounts to a commentary on interpretation as a semantical evocation, an analytic discourse whereby the analyst delivers the patient’s speech from the language of its symptom.

Lacan concludes his discussion of analytic technique saying, “This is surely the path by which a return to the use of symbolic effects can proceed in a renewed technique of interpretation”,32 and then proceeds to introduce the Indian concept of dhvani—“We could adopt as a reference here what the Hindu tradition teaches about dhvani, defining it as the property of speech by which it conveys what it does not say”.33

Lacan defines dhvani as a property of speech by which it conveys what it does not say. Dhvani is, in fact, an intrinsic feature of speech, where a meaning is evoked without being explicitly stated. Before going further, Lacan gives us an illustration of the notion in the form of a parable:

This is illustrated by a little tale whose näiveté, which appears to be required in such examples, proves funny enough to induce us to penetrate to the truth it conceals.

A girl, it is said, is awaiting her lover on the bank of a river when she sees a Brahmin coming along. She approaches him and exclaims in the most amiable tones: “What a lucky day this is for you! The dog whose barking used to frighten you will not be on this river again, for it was just devoured by a lion that roams around here . . .”.34

Initially, the story appears nonsensical. A girl sees a Brahmin and exclaims to him that the dog he fears was eaten by a lion. Readers who are puzzled by Lacan’s recounting of this story should also not fear, as Lacan has not left us in opacity. Rather, the clue to deciphering this illustration and the concept it signifies is given in Lacan’s footnote to dhvani, which reads: “I am referring here to the teaching of Abhinavagupta in the tenth century. See Dr. Kanti Chandra Pandey, “Indian Aesthetics,” Chowkamba Sanskrit Series, Studies, II (Benares: 1950)”.35

Lacan gives us the reference to the English translation of Pandey’s doctoral thesis on Indian aesthetics, which features a substantial chapter on Abhinavagupta’s interpretation of dhvani. Indeed, in this very chapter, we find the original story of the Brahmin at the river in a section titled “An Illustration of Dhvani”:

There is a garden on the bank of [the] river Godāvari. It is far from public haunt. A pair of lovers fixes it for a secret meeting at a particular time. One of the pair comes to this place a little before the fixed time. She sees a religious minded man going about here to collect flowers for worship. His sight is not quite welcome. She wants to drive him away without letting him know her intention.

A ferocious dog used to be kept here. She knew that the man was very much afraid of it. This dog, for some reason, is away from this place. She cleverly tries to explain the absence so as to scare him away and says:—

“O religious minded man! You can now roam freely over this place. For, the dog, of whom you were so afraid has been killed to-day by the proud lion, who, as you know very well, lives in the impervious thicket on the bank of Godāvari.”36

The original passage gives us essential background: the girl has ordained a meeting with her lover at a river away from the world, when she encounters a Brahmin whom she wants to drive away from the place. The story is an illustration of dhvani because the girl never explicitly says to the Brahmin that she would like him to leave. She conceals the truth in order to communicate what she wishes to evoke. Pandey gives his commentary:

It is not difficult to understand what meaning such a statement will have to such a person, as above described. Will the man, who fears a dog, freely move about at a place, where a lion, which has given a positive proof of his ferocious nature by killing the dog, is abroad? Will he, after hearing the above statement, stay on in the garden, or will he run away as quickly as possible? If the latter, is it not because of the negative meaning understood by him in a positive statement? And if so, the question arises: “Why does a positive statement have a negative meaning?” The exponents of the fourth power of the language maintain that the negative meaning, which the hearer gets, is due to Dhvani.37

In other words, the secondary meaning of the girl’s speech, while not stated as such, was heard by the Brahmin. Therefore, there is a function in speech that is primarily evocative, and this invocation is not itself said but heard.

Lacan interprets the story in the frame of absence/presence, which he remarked upon before as the source of meaning in language. Here, he says, “The absence of the lion may thus have as many effects as his spring—which, were he present, would only come once . . .”.38 There is an absence of the explicitly stated intent of the communication—the girl does not simply tell the Brahmin she wants him to leave. But amidst this absence of statement, the real intent of her message is present in the fact of her enunciation, however concealed its truth appears to be—“For the function of language in speech is not to inform but to evoke”.39

If speech can convey a coded message, then it functions on the basis of something given. Therefore, Lacan declares, “Speech is in fact a gift of language, and language is not immaterial. It is a subtle body, but body it is”.40 He then applies this to the analytic frame, suggesting that the patient pays the analyst a gift of money in exchange for the gift of speech as the “link between speech and the gift that constitutes primitive exchange”.41 This means that the patient does not merely pay the analyst for the rendering of professional services but engages in a symbolic exchange of gifts.

The symbolic exchange of gifts between two parties is what is known in Sanskrit as daksina, which means “a present or gift to Brahmanas (at the completion of a religious rite, such as a sacrifice)”, or simply a sacrament of universal sacrifice. The term is often applied in the context of the guru-disciple pedagogy or in sacramental rites. As a primitive exchange, daksina implies an economy of desire, where what is given is offered on the basis of one’s desire, and what is received is an excess that constitutes jouissance in its reception. In Indian rituals, this principle is illustrated in the devotee’s offering of daksina (whether in the form of money, fruit, or flowers) and the teacher or priest’s subsequent offering of prasād, a blessed object, often the return of what was offered by the devotee to the devotee. Prasād is defined as “that which is propitious”, or an object intended to convey blessing by virtue of having been consecrated and given. A return of the repressed in the real of the blessed.

Is this the meaning of transference? Is it prasad that the analyst offers when he propitiously punctuates the gift of the analysand’s speech? Is it the gift of speech which offers itself to be heard, so as to be given the jouissance that lingers in the speaking body, in the presence and the absence of words?

The hymns of the Vedas are crafted for the enunciation of a sacrificial rite, a genre of poetry known as dānastuti, the “praise of the gift”:

The [Rig Vedic] poet’s reward comes as a second-hand or indirect benefit of the success of his verbal labors: the patron should receive from the gods what he asked for, and he provides some portion of that bounty to the poet in recompense. This payment from his patron is sometimes celebrated by the poet at the end of his hymn, in a genre known as the dānastuti, literally “praise of the gift,” . . . .42

Dāna literally means “gift”—the daksina offered to the priest, the poet, or the analyst—and the discourse which celebrates its excesses. The Vedic poet may sing the praises of his patronage, but the analyst speaks to the free gift of the patient’s associations. What is given in the analytic exchange is no longer what the subject does not have, but the giving speech that constitutes the translation of consciousness. Therefore, the end of analysis is the completion of a ritual, or a prayer of changes, where the last word is a somatic syllable, an essential renunciation and realization.

The gift of speech is a prasād of prosody, a sound that leaves an echo of its truth to be heard at the water’s edge, where Narcissus loses face in the resonance of the real.

III. What the Thunder Spoke

The linguistic sign unites, not a thing and a name, but a concept and a sound-image. The latter is not the material sound, a purely physical thing, but the psychological imprint of the sound, the impression that it makes on our senses.

—Ferdinand de Saussure, Course in General Linguistics

To speak is already to go to the heart of psychoanalytic experience.

—Jacques Lacan, On the Names-of-the-Father

The final pages of Lacan’s opus are climactic, an epic moment of concluding that resounds with what the thunder said. Before we come to Prajāpati’s discourse, Lacan draws a parallel between psychoanalysis and Zen before making further inroads into Indian linguistics.

Commenting on the function of time in analysis, Lacan describes his earlier practice of “short sessions”, noting “that it bears a certain resemblance to the technique known as Zen, which is applied to bring about the subject’s revelation in the traditional ascesis of certain Far Eastern schools”.43 Lacan is likely referring to the Zen practice of sudden awakening (or satori) in which a disciple is spontaneously awakened through contemplation of a koan or hearing their Master’s paradoxical words. The techniques of sudden awakening are forms of crazy wisdom that provoke the subject’s enlightenment through an evocative use of speech that cuts through the barriers of the conventional mind.

A similar technique is found in the Dzogchen school of Tibetan Buddhism, where a Master points out the nature of the mind to the disciple through an oral transmission that, upon being heard, awakens the disciple to the truth of what was said. In the Vedantic tradition, the Master similarly speaks a great utterance (or mahāvākya)44 that either suddenly awakens the disciple who hears it or eventually awakens the disciple who chants its recitation.

For Lacan, the Eastern techniques are notable because they utilize speech in order to effect awakening, not at the level of didactic teaching but with the deepest pedagogical intent of an oral transmission of truth, receivable in the instant of being heard. They also function as examples of punctuation, the absence of which is a “source of ambiguity”45, as Lacan notes in regards to the lack of punctuation in Chinese canonical texts.

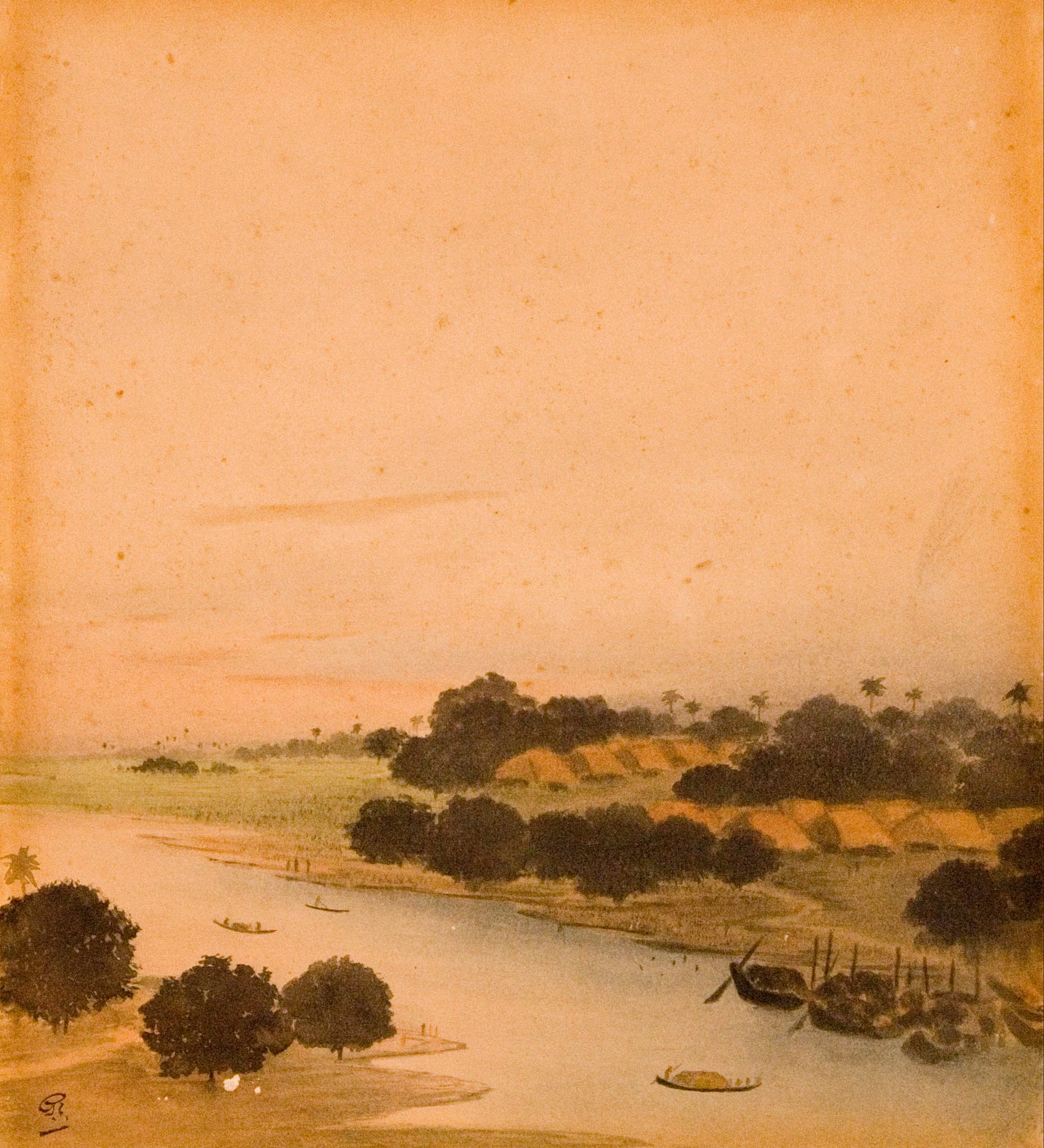

From here, Lacan returns to a discussion of Indian linguistics via the “classical problem posed to semantics in the determinative statement, ‘a hamlet on the Ganges,’ by which Hindu aesthetics illustrates the second form of the resonances of language”.46 Lacan’s footnote to this sentence reads, “This is the form called laksanalaksana”. The phrase appears mysterious: what is meant by a hamlet on the Ganges, and from where does Lacan derive this example? Our answer is, once again, in Pandey’s volume on Indian Aesthetics.

In a section titled “The Theory of Meaning Before the Acceptance of the Theory of Dhvani”, Pandey lists laksanāśakti as “the secondary power of words”:

Often we find in the existing literature linguistic constructions which convey a complex of ideas . . . The following illustration will clear the point in hand:—

gangāyām ghosah

(Hamlet on the Ganges)47

Gangāyām means “on the Ganges”, a rather straightforward translation. Pandey translates ghosah as “hamlet” in this context, but ghosah resonates in a signifying field that is relevant to our consideration. Ghosah carries various meanings in different textual contexts: the “thundering of clouds” (Rig Veda), “the whir of a bow-string” (Taittirīya Brāhmana), “a sound of speech” (Chandogya Upanishad), “proclamation” (Lotus Sutra), “a cry or roar of animals” (Rig Veda), and the “the sound of the recitation of prayers” (Mahābhārata). The usage of ghosah meaning “a hamlet; a station of cowherds” is found in the Mahābhārata. The exact origin of the phrase, gangāyām ghosah, is difficult to pinpoint, but it is a classic phrase that appears throughout canonical texts of Indian poetics (kavyashāstra). The example of the hamlet on the Ganges thus invokes the entire field of our discussion—the thunderous sound of speech itself as a resonance of meaning.

Pandey cites the phrase gangāyām ghosah in order to present the concept of laksanāśakti as a secondary power of language and as a concept that precedes Abhinavagupta’s articulation of dhvani. He writes:

. . . [T]he complex would be a meaningless jumble of ideas and not a harmonious whole, because it would stand for what in actual experience is not possible. For, a hamlet cannot exist on a current of water. Such sentences are, however, found in the standard works, not only in Sanskrit but in other languages also. And tradition finds a meaning, and a good one too, in them. For instance, when the aforesaid sentence is used, it is understood to mean that the hamlet is situated on the bank of the Ganges and that it is cool and holy.48

The hamlet on the Ganges illustrates the secondary power of language (laksanāśakti) by evoking what it means even while stating the impossible. Is this how speech approximates the real? The hamlet cannot literally exist on the Ganges, but the phrase “a hamlet on the Ganges” is immediately understood as a dwelling on the banks of the river. Pandey explains how this illustrates laksanāśakti:

To explain this third power of words, the Laksanasakti, is postulated. When some such words are intentionally used as do not arouse a harmonious complex of meanings in the mind of the hearer by means of conventional power of language: on the contrary, the meaning of one opposes that of another; under such circumstances the function of the secondary power of language is to arouse additional ideas as are necessary to put them in harmonious relation and to reveal the purpose of such use by the speaker. Thus the additional idea of the bank, aroused by this power, removes the lack of harmony; and the purpose of the speaker in using such construction is understood to convey the idea of coolness and holiness of the hamlet.49

Now, we must ask in what ways dhvani is distinguished from laksanāśakti? Or should they be considered parallel concepts? The notion of laksanāśakti precedes dhvani, if not anticipates it. However, the necessity for maintaining both concepts is contested in the traditional literature. The primary distinction between dhvani and laksanāśakti is the difference between “suggestiveness” and “secondary meaning”. Pandey summarizes one critical position:

Laksana is defined by some as a power of language, which arouses the consciousness of any meaning that is different from the conventional, but has invariable concomitance with it (abhidheyāvinābhūtapratītih). The followers of this definition deny the difference of the suggestible meaning from the secondary . . . The opponents, therefore, maintain that in the case of the so called suggestible meaning, in the arousal of which the different stages from the conventional to the contextual and from that to the secondary are not noticeable, is really the secondary meaning; because the so called suggestible meaning also is one that has invariable concomitance with the conventional.50

This position holds that dhvani is an unnecessary concept, since its implication is already subsumed in the earlier concept of laksanā. In other words, the connotative and suggestive aspect of language is an inherent power, not a distinct property of suggestibility itself. A variant of this position proposes laksanalaksanā as a substitute for dhvani. Until now, Pandey has referenced the term laksanāśakti (“secondary power of language”) and has used this interchangeably with laksanā. Here, he introduces laksanalaksanā as a “variety of laksanā” and a “secondary power”. This is to say that laksanalaksanāis the most precise reference for that power of language (laksanāśakti) which is secondary in nature. Pandey says:

The ordinary secondary meaning is got out of a construction by simple laksana, for instance, the meaning of “Gangāyām ghosah” as “Gangātīre ghosah”. But the meaning that “Ghosa” is cool, holy and so on, is got by laksanalaksana. That is, the secondary power of language, after having aroused the secondary meaning, the bank, works again to arouse the additional ideas of coolness, etc. The rise of suggestible meaning, therefore, according to the opponent, can be explained by assumption of the said variety of laksana.51

Laksanalaksanā and dhvani both describe the signifying function of speech—that what is said slides in a chain of signifiers that always stand for another signifier. If we take the term ghosa (translated as “hamlet”) at the level of the signifier, then we see a signifying chain—ghosa not only means “hamlet” but also “sound of speech”, “the thundering of clouds”, and “proclamation”. As such, it appears that the classical example of a hamlet on the Ganges illustrates the function of speech in its own language.

Pandey concludes his examination of the debate between laksanalaksanā and dhvani with the following summary:

The ideas, which the suggestive power of words is intended to arouse, are certainly different from those which the secondary power is said to give rise to. The necessary condition for the power to operate in the latter case is the apparent lack of harmony in the different constituents of a sentence. But the former does not presuppose this condition. If a statement is intended to suggest what is not directly expressed, or rather under circumstances cannot be so expressed, but is suggested by a peculiar arrangement and choice of the words, it requires the power of visualization (Pratibhā) in the hearer, and not simply the knowledge of the secondary convention (Laksanā). Hence the distinction between Laksanā and Dhvani has got to be admitted.52

It is simple enough to accept that dhvani and laksanā describe different aspects of the signifying process inherent in the field of language and invoked in the function of speech. Notably, Pandey uses the term pratibhā to describe the “power of visualization in the hearer” that dhvani evokes. Pratibhā means “reflection”, “brilliance”, “understanding”, and “genius, especially poetic genius”. Pratibhā evokes the mirror stage as the genesis of language, where the spatial lure of identification becomes a grammatical and pronominal reflex.

Is it pratibhā that the analyst must cultivate as he listens to the free associations of the patient? Must he not only auscultate but see their sonorous rhythms, metrical arrhythmias, and slippery spheres? Does this explain Lacan’s desire to formalize the unconscious with topology?

In the penultimate page of his essay, Lacan writes:

To say that this mortal meaning reveals in speech a center that is outside of language is more than a metaphor—it manifests a structure. This structure differs from the spatialization of the circumference or sphere with which some people like to schematize the limits of the living being and its environment: it corresponds rather to the relational group that symbolic logic designates topologically as a ring.

If I wanted to give an intuitive representation of it, it seems that I would have to resort not to the two-dimensionality of a zone, but rather to the three-dimensional form of a torus, insofar as a torus’ peripheral exteriority and central exteriority constitute but one single region.53

Lacan sees the field of language and the function of speech as a singular structure, a region where the contours of dhvani and laksanalaksanā slide across a sphere of signification. In Lacan’s structural assertion of the unconscious, we discover a resolution beyond the traditional debates of Indian grammarians, where secondary powers and suggestiveness are free-floating across the smooth surface of circular speech.

Before concluding what could be called his dharmic exposition, Lacan articulates the place of psychoanalysis in the very locus of the human being:

Psychoanalytic experience has rediscovered in man the imperative of the Word as the law that has shaped him in its image. It exploits the poetic function of language to give his desire its symbolic mediation. May this experience finally enable you to understand that the whole reality of its effects lies in the gift of speech; for it is through this gift that all reality has come to man and through its ongoing action that he sustains reality.

If the domain defined by this gift of speech must be sufficient for both your action and your knowledge, it will also be sufficient for your devotion. For it offers the latter a privileged field.54

Lacan then proceeds to quote a passage from the Brihadāranyaka Upanishad, titled “What the Thunder Said”. In this section, Prajāpati (the god of thunder and lord of all creatures) responds to the request of the devas (gods), the humans, and the asuras (demons), who, upon finishing their novitiate with Prajāpati, begged of him, “Speak to us”. To each of them, Prajāpati utters the syllable, “Da”, and then asks, “Did you hear me?” The devas answer, “Thou hast said to us: Damyata, master yourselves—the sacred text meaning that the powers above are governed by the law of speech”. The humans answer, “Thou hast said to us: Datta, give—the sacred text meaning that men recognize each other by the gift of speech”. And the asuras answer, “Thou hast said to us: Dayadhvam, be merciful—the sacred text meaning that the powers below resound to the invocation of speech”.55

Do the devas, humans, and asuras each hear their own message, returning to them in an inverted form, perfectly resonant with subjective meaning? For Prajāpati utters the same syllable for each to hear in accordance with their own ear of heart.

Prajāpati’s utterance (“Da”) and the response heard by the novitiates (“damyata, datta, dayadhvam”) was famously quoted by T.S. Eliot in 1922 in the concluding stanzas to “The Waste Land”. It may be that Lacan first encountered this Upanishadic reference from reading Eliot’s poem, as he does cite a different poem from Eliot, “The Hollow Men”, earlier in the essay.56 However, Lacan’s engagement with the Upanishads is already well-established, as he cites the mahāvākya “Tat Tvam Asi” (“Thou Art That”) in the concluding lines of “The Mirror Stage as Formative of the I Function” just four years before delivering “The Function and Field of Speech and Language in Psychoanalysis”. Nearly ten years after the writing of “Function and Field”, Lacan returns to this Vedāntic utterance in Seminar X, in the chapter “Buddha’s Eyelids”—“Tat tvam asi, the that which thou dost recognize in the other is thyself, is already set down in the Vedānta”.57

The syllable “Da” means “the one who gives” and “what is given”, and with each utterance, Prajāpati gives the gift of speech to devas, humans, and asuras. “Da” is the root-syllable in the variants they hear: damyata is the calling to mastery, datta is the calling to generosity, dayadhvam is the calling to mercy. Prajāpati speaks the Name-of-the-Father—Da—and thus invokes the laws of speech in the three realms. For who is Prajāpati if not Brahma himself, he who sovereigns the symbol of creation? Is it he from whom the seed of the world springs from formless resonance into the form of sound?

Prajāpati speaks a proper name in a divine voice, and thus translates the signifier in the real. The name and the voice form the binary structure of speech, as Lacan notes, “The relationship between the proper name and the voice must be situated in language’s two-axis structure of message and code, to which I have already referred . . . It is this structure that makes puns on proper names into witticisms”.58

The devas, humans, and asuras hear the Name-of-the-Father, echoing from the Other in their subjective fields. Thus, they receive the inheritance of the law through a morphological family, a morpheme unified in a common root from which they are each derived. Prajāpati says, “Da”, but the beings of the three worlds receive their own message, in a form suitable for baptism—as it is the holy spirit of the signifier that falls from the Father’s lips to bless his children in the eucharist of speech. Prajāpati thus returns the repressed signifier to his children in its primordial text, a transmission of filial inheritance and spiritual regeneration. It is the tone of his divine voice that slides the signifier across the register of the real.

This is why it is said, in the Chāndogya Upanishad, that “[w]hen the gods and the demons, both descendants of Prajā-pati, contended with each other, the gods took hold of the udgītha, thinking, with this, we shall overcome them”.59 Here, the reference to gods and demons is condensed within a single signifier—devāsurā—where its usage depicts the existential conflict between light (illumination) and dark (ignorance) within the human being. This section of the Upanishad is titled “Life (Breath) as The Udgītha”, where udgītha refers simultaneously to the breath, speech, and the syllable Om. The relationship between speech and breath is elucidated in the third section:

. . . [O]ne should meditate on the diffused breath as the udgītha. That which one breathes in, that is the in-breath; that which one breathes out, that is the out-breath. The junction of the in-breath and the out-breath is the diffused breath. The diffused breath is the speech. Therefore, one utters speech, without in-breathing and without out-breathing.60

The function of speech originates in the still-point, the median void between inhalation and exhalation, where a pervasion of syllabic resonance is already heard in the heart of what is spoken. The notion of udgītha thus brings us to the very essence of speech as a circulation of sound. In the Chandogya Upanishad, Prajāpati admonishes the devas and asuras to meditate upon Om as the basis of speech, but in the Brihadāranyaka Upanishad, Prajāpati commands “Da”. What is the relationship between Om and Da? “Om” is more accurately transliterated as aum, where we see its tri-syllabic structure. These three syllables correspond to various trinities in Indian thought—Brahma-Vishnu-Shiva; waking, dreaming, sleeping, and so on. Dissecting this further, the syllable “a” is most prominent in the pronunciation of “Da” (and this may also be why the Tibetan tradition has adopted “A” as their primordial syllable)61; the combined sound of “a” and “oo” becomes the long vowel (ō)at the root of “Om”; and the “m” is the origin of the syllable “Ma”.

The modern spiritual master, Adi Da, dissects the Om-sound into three primary syllables constitutive of the mahāmantra—Om Ma Da—where Om represents the “Self-Father”, Ma the “Mother-Power”, and Da the “True and First Son” of their union.62 If we interpret this as a homology for the Christian trinity, then “Om” is the Father, “Ma” is the Holy Spirit, and “Da” is the Son. As the “son”, “Da” functions as the condensation or epitome of “Om” and “Ma”, and thus signifies via inheritance the totality of reality.

If we translate this paradigm in psychoanalytic terms: Om is the Name-of-the-Father, Ma is the holy spirit of the signifier, and Da is the signifier in the real. “Om” is the name of the symbolic, “Ma” is the measure of the imaginary, and “Da” is the name of the real. Together, the three syllables constitute a primordial structure of kinship that originates in the three registers of human reality. As Lacan notes, “any analyzable relationship . . . is always inscribed in a three-term relationship”.63

If “Da” is the Son, then Prajāpati’s utterance is the birth of language, an incarnation made of love. As Lacan says, “Giving someone a child as a gift is the very incarnation of love. For humans, a child is what is most real”.64 Therefore, “Da” constitutes, at the level of the signifier and its signified, the very gift of speech.

Adi Da continues his exegesis by expounding on the significance of Da as a “name” (a name he notably adopts as his own appellation)—specifically a function of the name that stands as a signifier for the real:

The One and Only . . . Divine Person . . . Is, By Tradition, Named—In Order To Be Invoked By Humankind.

Therefore, Traditionally, The Divine Source and Person Has Been (and Is) Named (and Invoked) By Many Names. In The Practice Of Some Traditions, The Divine Source and

Person Is Named “Da”.

The Name “Da” Is A Name Of Real (Acausal) God65 (or The Necessarily Divine Reality, Truth, and Person That Is).

This Name Has Appeared Spontaneously To Many (and Many Kinds Of) Realizers, In Traditional “Religious” and Spiritual Cultures All Over the “world”, During and Ever Since Ancient times.

The Name “Da” Signifies (or Points To) The Transcendental (and Inherently Spiritual) Divine Reality, Truth, and Person—As The “Giver” Of Life, Liberation, Blessing, Help, Spirit-Baptism, and Awakening Grace.66

Adi Da’s commentary emphasizes the function of the name as the means for invocation. Lacan has already given us the link between the name and the function, when he says, “the name of the father creates the function of the father”,67 a point he elaborates upon in “Function and Field”: “It is in the name of the father that we must recognize the basis of the symbolic function which, since the dawn of historical time, has identified his person with the figure of the law”.68 Is it not Prajāpati, the father of creation, who utters this syllable to his children?

Adi Da also suggests that “Da” is a universal name, found in cultures around the world since antiquity. I read this statement in the tone of an oracular vernacular rather than the silence of a scholastic notation. We cannot verify the truth of the statement with anthropological serums. The real of Adi Da’s utterance is, in fact, located in the very function of the name, as Lacan has already remarked: “A name . . . is a mark that is already open to reading—which is why it is read the same way in all languages—printed on something that may be a subject who will speak, but who will not necessarily speak at all”.69 I read Lacan’s reference to the name as the mark in the code of Sanskrit etymology, where lingam means “phallus” and “mark”. If the phallus is the signifier of desire that raises its primordial rank in the Name-of-the-Father, then the question of the name is the question of consciousness.

The syllable “Da” may indeed be at the very origin of spoken language, already on the tip of every tongue. In Sanskrit, “Da” is a dental syllable, spoken with the tongue behind the front teeth—a location that forms a circuit of conductivity in Indian and Daoist yoga.70 Commenting on this yogic mudra, Adi Da references Patanjali’s Hatha Yoga Pradipika:

The Hatha Yoga Pradipika and other similar yogic texts speak of the soma as “the nectar of the moon.” By pressing the tongue up through the roof of the palate and closing off the passage in the head above the sinuses and above the mouth, and entering into meditation, the yogis prevent the nectar of the moon from burning up in the “sun,” which is the lower body or digestive region, the digestive fire of the navel.71

The association between speech and soma was originally formulated in the Rig Veda. In verse VIII.100.10-11, speech is likened to the milking of a cow:

When Speech, saying indistinguishable things, sat down as gladdening ruler of the gods, she milked out in four (streams) nourishment and milk drinks. Where indeed did the highest of hers go?

The gods begat goddess Speech. The beasts of all forms speak her. Gladdening, milking out refreshment and nourishment for us, let Speech, the milk-cow, come well praised to us.72

The goddess Speech (Vāc) is described as a “milk-cow”, who pours forth a somatic stream of words. The context of these verses is cryptic but revolves around the pressing of soma for the ritual sacrifice that is central to the Vedic hymns. Speech is thus regarded as an oblation, a devotional offering sacramentally milked for the gods.

Unlike most of the hymns in the Rig Veda, the goddess Vāc speaks in the first-person (aham) in a self-confessional mode known as ātmastuti. In verses 2, 3, and 4, Vāc speaks of herself as bearing the “swollen soma”:

2. I bear the swollen soma, I Tvastar and Pūsan and Bhaga. I establish wealth for the man offering the oblation, who pursues (his ritual duties) well, who sacrifices and presses.

3. I am ruler, assembler of goods, observer foremost among those deserving the sacrifice. Me have the gods distributed in many places—so that I have many stations and cause many things to enter (me).

4. Through me he eats food—whoever sees, whoever breathes, whoever hears what is spoken. Without thinking about it, they live on me. Listen, o you who are listened to: it’s a trustworthy thing I tell you.73

If the Rig Veda casts Vāc in feminine, then how do we understand the relationship between speech and the father—for Vāc herself says, “I give birth to Father on his head; my womb is in the waters, in the sea.”74 Is it Vāc who embodies the name of the father? Later texts attempt to resolve this riddle by placing Vāc as either the daughter or consort of Prajāpati, where Vāc is seen as the manifestation of the creation generated by Prajāpati.

Is Vāc the function of speech through which the concealed truths of creation are penetrated in the names-of-the-father? Is “Da” that dawning syllable of the speech circuit, the locutional link generated in the current of discourse? Is “Da” the soma we press in our own mouths to sever umbilical ties?

“Da” is spoken by children before they speak in sentences—in English, “Da” has phonetic resonance with “Dad” (in British English, “Da” functions as a direct reference to one’s father) and in Sanskrit dādā is the signifier for one’s paternal grandfather.75 It may be with this intention that Lacan recalls the child’s game—Fort! Da!—only two pages prior to Prajāpati’s speech:

These are occultation games which Freud, in a flash of genius, presented to us so that we might see in them that the moment at which desire is humanized is also that at which the child is born into language.

. . . We can now see that the subject here does not simply master his deprivation by assuming it––he raises his desire to a second power . . . the child thus begins to become engaged in the system of the concrete discourse of those around him by reproducing more or less approximately in his Fort! and Da! the terms he receives from them.76

In German, “Fort” means “gone” and “Da” means “there”, a spoken alternation of absence and presence. As the child receives the function of his speech from the field of the Other, the novitiates receive the gift of initiation in Prajāpati’s spoken deliverance. As novices, the gods, humans, and demons are completing their training for entry into a religious order, when they ask Prajāpati to grant them the initiation of their submission. This context is not lost upon Lacan, who on the preceding page mentions the sublimity of the psychoanalytic undertaking and the ordeal of its training:

Of all the undertakings that have been proposed in this century, the psychoanalyst’s is perhaps the loftiest, because it mediates in our time between the care-ridden man and the subject of absolute knowledge. This is also why it requires a long subjective ascesis, indeed one that never ends, since the end of training analysis itself is not separable from the subject’s engagement in his practice.77

Lacan is thus presenting psychoanalysis as an initiatory rite and a rite of passage, a training homologous to a novitiate’s entry in a religious order. Indeed, Freud had formed a secret order of initiates, to whom he gave seven rings. Earlier in his essay, Lacan mentions this fact in a passing remark about Ernest Jones, who is “the last survivor of those to whom the seven rings of the master were passed”.78

It is as the initiatory rite that the function of the name is discovered as a transferential transmission by which an esoteric order is founded. As Lacan says, “We are aware of the use made in primitive traditions of secret names, with which the subject identifies his own person or his gods so closely that to reveal these names is to lose himself or betray these gods; and what our patients confide in us, as well as our own recollections, teach us that it is not at all rare for children to spontaneously rediscover the virtues of that use”.79 The guarding of the name is the protection of the holy, the setting apart of the esoteric from the exoteric via the passwords of sacred law.

In the Rig Veda, the notion of the secret name is posed in a hymn on sacred speech, which opens with the following stanzas:

1. O Br̥haspati, (this was) the first beginning of Speech: when they [the seers] came forth, giving names. What was their best, what was flawless—that (name), set down in secret, was revealed to them because of your affection (for them).

2. When the wise have created Speech by their thought, purifying her like coarse grain by a sieve, in this they recognize their companionship as companions. Their auspicious mark has been set down upon Speech.80

Is “Da” the secret name of the Father uttered for initiation? Does its invocation restore the devas, the humans, and the demons to the laws that govern their worlds? Is it the nature of “Da” as a dawning signifier in the real that grants it the gift of inauguration? If the real resists symbolization absolutely, then it can only be called upon by name. This is why Adi Da refers to “Da” as a “Meaningless Pointer (or Name)”,81 emphasizing its phonetic, rather than symbolically meaningful, function. The meaningless phonetic of the signifier is the meaning of mantra—a syllable behind thought that is spoken for the resonance of its invocation.

We return to an enigmatic riddle of meaning. Is meaning intrinsic to the phonetic of the word and thus to the function of speech? Or does meaning reside in the field of linguistic implication, in the grammatical rule of the spoken, where what is heard is the suggestion of the enunciation? This is the rebus that Indian grammarians have attempted to read in their articulations of dhvani, which indicates the “articulate sound” because the word produces “sound waves very much like the ring of a bell”.82 Pandey writes that “the grammarians explain the sound-sensation as due to the contact of one of the sound-waves, proceeding in a regular series from the source, with the drum of the ear . . . Just as sound comes to the hearer’s consciousness through succession of meanings, the conventional, the contextual and the secondary”.83

The grammarians place sound as the universal component of meaning and thus attribute meaning to a function of speech. Here, dhvani emerges as an intrinsic suggestibility that is conveyed in the resonances the word evokes. As Lacan notes, a signifier always stands for another signifier. The signifier constantly slides across the signifying chain and thus elides a singular meaning. A signifier functions at the level of speech as the totality of what it can signify in the field of language. As such a slippery sphere, it is the unseen but audible that makes itself known across the field of meaning, where the signified grasps the last tail of its winding signifier. “For these chains are not of meaning but of enjoy-meant [joui-sens] which you can write as you wish, as is implied by the punning that constitutes the law of the signifier”.84

The phonetic mechanism of speech is explained by Indian grammarians as a function of “the universal sound, called Sphota . . . According to them, the awareness of the Sphota of a word, is necessary for the consciousness of meaning of a word”.85 The concept of sphota was popularized by the Indian linguist Bhartrihari in the fifth century CE, and later expanded upon by Abhinavagupta. Sphota means “bursting”—it is the eruption of meaning that flashes forth in the sound of the word.86 The notion of sphota resonates with the theory of spanda in Kashmir Saivism, which Abhinavagupta popularized. Spanda bears the connotations of “throbbing” and “palpitation”, and is used to mean the “pulse of the supreme level of speech” and the “pulse of the vibratory universe”. It is the causal root of language and suggests the heart as the circulatory locus of sacred speech, an atrial fibrillation of meaning. As Lacan says, “I know better than anyone that we listen for what lies beyond discourse, if only I take the path of hearing, not that of auscultating”.87

Language is the construction of a symbolic order, but its spoken sound is heard in the real. Therefore, the function of speech is not the communication of meaning but an invocation by name. When Prajāpati thunders “Da”, his speech erupts the sound with a flash of meaning, heard by each in the tone meant for their listening. Prajāpati thus “shatters discourse only in order to bring forth speech”88 in a sudden storm of language.

Speech is the primal sound of cosmic existence, or nāda brahma. Adi Da thus positions “Da” in precisely this category when he makes it synonymous with “Om” as the sound-vibration at the root of the cosmos. He writes:

The Cosmic Divine Sound-Vibration “Om” (or “Da-Om”, or “Da”) Corresponds To and Signifies and Points (Beyond Itself) To The Native (Soundless, Silent) Feeling (and The Very Condition) of Being (Prior To All Separate ‘I’-ness) That Is The . . . Root Of All Vibratory Modifications (and, Therefore, Of all sounds, and Of all thoughts, or all ideas, including the “I”-thought, or the “Separate-self”-idea, and Of all things, or Even Of all the kinds of conditional forms and states) In The Cosmic Domain.89

In other words, “Da” and “Om” are sounds voiced in the real, that even when spoken, resist symbolization utterly. The assertion of “Da” as a signifier in the real is elaborated in the Brahmana following Prajāpati’s discourse. After declaring Brahman as “the True or Real”, the Upanishad equivocates Prajāpati with Brahman, and locates the real in the locus of the heart. The Brahmana structures this argument by elaborating on “Da” as the central syllable of the tri-syllabic hridayam—a word meaning “heart center”:

This is Prajapati (the same as) this heart. It is Brahman.90 It is all. It has three syllables, hr, da, yam. Hr is one syllable. His own people and others bring (presents) to him who knows this. Da is one syllable. His own people and others give to him who knows this. Yam is one syllable. He who knows this goes to the heavenly world.91

“Da” is the core syllable of the Sanskrit word for the heart––hridaya. Yet, hridaya does not merely signify the physical or spiritual heart of man. Hridaya is all that is held within the chest, a “divine knowledge” and “guarded secret” of one’s “innermost desire”. As it is said in the Nārāyana Sūktam of the Mahānārāyana Upanishad:

The Heart, the perfect seat of meditation, resembles an inverted lotus bud.

In the region below the throat and above the navel there burns a fire from which flames are rising up. That is the great support and foundation of the Universe.

It always hangs down from the arteries like a lotus bud. In the middle of it there is a tiny orifice in which all are firmly supported.

In the middle of it there is a great fire with innumerable flames blazing on all sides which first consumes the food and then distributes it to all parts of the body. It is the immutable and all-knowing.

Its rays constantly shoot upwards and downwards. It heats the body from head to foot. In the middle of it there is a tongue of fire which is extremely small.

That tongue of fire is dazzling as a streak of lightning in the midst of a dark cloud and as thin as the awn at the tip of a grain of rice, golden bright and extremely minute.

In the middle of that tongue of flame the Supreme Self abides firmly. He Is God. He is the Immortal, the Supreme Lord of all.92

The heart that hangs an inverted lotus below the throat is the speech that thunders the syllable to lumen the real. We receive the function of speech in an inverted form, hanging on symbolic threads of meaning, echoing in the field of the Other. But when the real speaks its own name aloud, it gives a baptism in tongues of fire, that its eternal law may be heard in conveyance of its submission, gift, and grace. As Lacan clarifies in a footnote to the Upanishadic passage, “It should be clear that it is not a question here of the ‘gifts’ that novices are always supposed not to have, but of a tone that they are, indeed, missing more often than they should be”.93 What is to be understood is not a meaning but a hearing, a tonal truth that transfers itself in Prajāpati’s oral transmission to the ears of the novices.

At last, Lacan concludes, this is “what the divine voice conveys in the thunder: Submission, gift, grace. Da da da. For Prajapati replies to all: ‘You have heard me”.94 There is no absence of understanding or confusion of tongues, no babbling aspirations for an other world. Prajāpati translates the Oedipal errors of ignorance, love, and hatred into submission (to the laws of speech), gift (of recognition through speech), and grace (of the invocation of speech). Thus, the three worlds are purified by Prajāpati’s utterance, as thunder restores a light in the dark cloud.

The beings of the world thus find the law in the place of the real, where they currently stand. A hamlet appears on the Ganges is always already the case. There, in the current of sound, betwixt the knots of head and heart, churns the throated consonance of a nectarous nādī—immortal in its shapeless synecdoche.

The word vāk first appears in the Rig Veda, in reference to the goddess Vāc (as a personification of speech) and in an explanation of the four divisions of speech: parā (transcendental sound), paśyantï (vibrational sound), madhyamā (mental speech), vaikharï (audible speech).

S. Radhakrishnan, The Philosophy of the Upanisads (George Allen and Unwin, 1953), 20.

Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: Book XIX . . . or Worse, ed. Jacques-Alain Miller, trans. A.R. Price (Polity Press, 2022), 53.

Lacan, Seminar XIX, 54.

Jacques Lacan, On the Names-of-the-Father, ed. Jacques-Alain Miller, trans. Bruce Fink (Polity Press, 2013), 17. Lacan delivered his talk, “The Symbolic, the Imaginary, and the Real” on July 8, 1953. This talk should be seen as the true preface to “The Function and Field of Speech and Language in Psychoanalysis”, as Lacan’s concluding remark makes clear: “. . . [I]t was merely an introduction, a preface to what I will try to discuss more completely and more concretely in the report that I hope to deliver to you soon in Rome on the subject of language in psychoanalysis”. (Lacan, 39).

Lacan, Seminar XIX, 55.

Lacan, Seminar XIX, 55.

Lacan, Seminar XIX, 62.

Lacan, Seminar XIX, 64.

Radhakrishnan, The Principal Upanisads, 62.

Jacques Lacan, Écrits: The First Complete Edition in English, trans. Bruce Fink (W.W. Norton and Company, 2006), 198.

Lacan, Écrits, 205.

Abhinavagupta (950-1016 CE) was an Indian polymath who made influential contributions to Indian arts and culture, especially in the study of linguistics and the philosophy of Kashmir Shaivism.

Pānini (c. fourth-seventh centuries BCE) was an Indian grammarian who is rightly regarded as the father of linguistics.

Ferdinand de Saussure, On the Use of Genitive Absolute in Sanskrit, trans. Ananta Ch. Shukla (Common Ground Research Networks, 2018), ix.

Ferdinand de Saussure, Course in General Linguistics, ed. Perry Meisel and Haun Saussy, trans. Wade Baskin (Columbia University Press, 2011), 9.

Lacan, Écrits, 206.

Lacan, 209.

Lacan, 209.

Lacan, 221.

Lacan, 221.

Lacan, 221-222.

Stephanie W. Jamison and Brereton, The Rigveda: The Earliest Religious Poetry of India, Vol. I (Oxford University Press, 2014), 70.

Lacan, Écrits, 222-223.

Lacan, 228.

Lacan, 229.

Lacan, 236. See Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Elementary Structures of Kinship (Beacon Press, 1969).

Lacan, 238.

Lacan, 238.

Lacan, 243.

Lacan, 243.

Lacan, 243.

Lacan, 243.

Lacan, 243-244.

Lacan, 267.

Kanti Chandra Pandey, Comparative Aesthetics, Vol. I: Indian Aesthetics (Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series, 1959), second ed., 269-270.

Pandey, Comparative Aesthetics, 270.

Lacan, Écrits, 244.

Lacan, 247.

Lacan, 248.

Lacan, 256.

Jamison and Brereton, The Rigveda, 9.

Lacan, Écrits, 260.

Mahāvākya literally means “great utterance”. In the context of Advaita Vedānta and the Upanishads, a mahāvākya is an aphoristic statement that when spoken or heard awakens the listener to the real (Brahman). In later usage, mahāvākya gained the general connotation of “discourse”.

Lacan, 258.

Lacan, 261.

Pandey, Comparative Aesthetics, 267.

Pandey, 268.

Pandey, 269.

Pandey, 287-288.

Pandey, 289-290.

Pandey, 291.

Lacan, Écrits, 263-264.

Lacan, 264-265.

Lacan, 265.

Roudinesco notes that in the autumn of 1940, Lacan had “begun to study the English language with René Varin” and “started translating some of the poems of T.S. Eliot” with his former analysand, Georges Bernier. See Elisabeth Roudinesco, Jacques Lacan, trans. Barbara Bray (Columbia University Press, 1997), 159.

Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: Book X, Anxiety, ed. Jacques-Alain Miller, trans. A.R. Price (Polity Press, 2014), 223.

Lacan, Écrits, 487.

Radhakrishnan, The Principal Upanisads, 339.

Radhakrishnan, 342-343.

See Chögyal Namkhai Norbu, The Crystal and the Way of Light: Sutra, Tantra, and Dzogchen (Shambhala Publications, 1999).

Adi Da Samraj, The Dawn Horse Testament, New Standard Edition (Dawn Horse Press, 2004), 871.

Jacques Lacan, On the Names-of-the-Father, 27.

Lacan, 49.

In his writings, Adi Da consistently uses the phrase “Real God” or “Real (Acausal) God” to signify the non-dual nature of the real, distinguishing it from Judeo-Christian conceptions of a Creator. In his usage, “Real God” is synonymous with the Vedāntic “Brahman”.

Samraj, The Dawn Horse Testament, 863.

Lacan, On the Names-of-the-Father, 44.

Lacan, Écrits, 230. This instance marks the first instance of Lacan’s now infamous phrase, “Name-of-the-Father”.

Lacan, On the Names-of-the-Father, 75.

On the yogic mudra of the tongue, Adi Da writes: “This is a characteristic of an Awakened man: The tongue touches the roof of the mouth, the eyes see the Light, and the mind is absorbed in Bliss . . . Even speaking requires lifting the tongue from the roof of the mouth. So, if you are gossiping and speaking craziness and indulging negativity in speech, you are not eating, you are not being sustained. Speech should sustain you. Your life of speech should be a form of your communication in Divine Communion”. See Bubba Free John, The Eating Gorilla Comes in Peace (Dawn Horse Press, 1978), 235-236. An identical emphasis is found in the Daoist tradition, where the mudra of the tongue behind the teeth completes the circuit of the microcosmic orbit by connecting the Ren (Conception) and Du (Governor) vessels.

Bubba Free John [Adi Da Samraj], The Eating Gorilla Comes in Peace (Dawn Horse Press, 1978), 516.

Jamison and Brereton, The Rigveda, 1210.

Jamison and Brereton, 1603.

Jamison and Brereton, 1604.

In the Gujarati language, the maternal grandfather is known as nānā. Thus, only the paternal grandfather bears the designation of the double-syllable, dādā, since it is from the paternal that the law of inheritance is passed from generation to generation.

Lacan, Écrits, 262.

Lacan, 264.

Lacan, 243.

Lacan, 246-247.

Jamison and Brereton, The Rigveda, 1497.

Samraj, The Dawn Horse Testament, 863.

Pandey, Comparative Aesthetics, 281.

Pandey, 281.

Jacques Lacan, Television, ed. Joan Copjec, trans. Denis Hollier, Rosalind Krauss, and Annette Michelson (W.W. Norton and Company, 1990), 10.

Pandey, Comparative Aesthetics, 281.

Sphota and dhvani are interdependent concepts. In one view, dhvani is used in reference to “the last sound of the word, which is primarily responsible for the manifestation of Sphota. The exponents of the theory of suggested meaning, following this use by grammarians, have used the word Dhvani for both the suggestive word and the suggestive meaning, for the simple reason that just as the last sound brings the Sphota to the hearer’s consciousness, so does the suggestive word or the suggestive meaning”. (Pandey, Comparative Aesthetics, 281-282).

Lacan, Écrits, 515.

Lacan, 260.

Samraj, The Dawn Horse Testament, 866.

In the Upanishads, Prajapati is regarded as a form of Brahman, the self-existing and non-dual reality. In Upanishadic thought, the heart is understood as the locus of the real. Thus, this passage emphasizes Prajapati as the transcendental spirit in the heart of man.

Radhakrishnan, The Principal Upanisads, 291-292.

Franklin Jones [Adi Da Samraj], The Method of the Siddhas (Dawn Horse Press, 1973), xvi-xviii. Adi Da places these verses as the “Invocation” preceding his first collection of discourses. His rendering of the Nārāyana Sūktam was drawn from an English translation of the Sanskrit original published in The Mountain Path journal by Sri Ramanasramam in 1972. The Nārāyana Sūktam comprises sections one, thirteen, and twenty-three of the Mahānārāyana Upanishad.

Lacan, Écrits, 268.

Lacan, 265.

Bibliography

Apte, Vaman Shivaram. The Practical Sanskrit-English Dictionary, revised and enlarged edition. Prasad Prakashan, 1957-1959.

Eliot, T.S. The Waste Land. Boni and Liveright, 1922.

Jamison, Stephanie W., and Joel P. Brereton. The Rigveda: The Earliest Religious Poetry of India. Vol. I. Oxford University Press, 2014.

Jones, Franklin [Adi Da Samraj]. The Method of the Siddhas. Dawn Horse Press, 1973.

Lacan, Jacques. Television: A Challenge to the Psychoanalytic Establishment. Edited by Joan Copjec. Translated by Denis Hollier, Rosalind Krauss, Annette Michelson, and Jeffrey Mehlman. W.W. Norton and Company, 1990.

Lacan, Jacques. Écrits: The First Complete Edition in English. Translated by Bruce Fink. W.W. Norton and Company, 2006.

Lacan, Jacques. On the Names-of-the-Father. Edited by Jacques-Alain Miller, translated by Bruce Fink. Polity Press, 2013.

Lacan, Jacques. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: Book X, Anxiety. Edited by Jacques-Alain Miller, translated by A.R. Price. Polity Press, 2014.

Lacan, Jacques. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: Book XIX . . . or Worse. Edited by Jacques-Alain Miller, translated by A.R. Price. Polity Press, 2022.

Pandey, Kanti Chandra. Comparative Aesthetics. Vol. I: Indian Aesthetics, second ed. Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series, 1959.

Pānini. Astādhyāyi of Pānini. Translated by Sumita Katre. Motilal Banarsidas, 2015.