Tabla music is a scriptless verse—a composition of syllables without form. Tabla players learn to play primarily through recitation of rhythmic syllables known as bols. In the context of classical tabla compositions, the bols are arranged in time cycles with nuances of syllabic emphasis. Tabla music contains an intrinsic polarity, a constant motion between male and female elements, open and closed sounds, meditation and prayer. The ability to render the rhythmic and melodic emphases of tabla composition through a purely percussive means is unique to tabla as an instrument.

Aloke Dutta refers to this realization as “poetic drumming”, a point he emphasizes in his teachings and illustrates in his music. His third album, Scriptless Verse, is a classic example of the beauty and power of pure tabla music. Aloke demonstrates how tabla transcends the boundaries of percussion and enters the realm of melody, and ultimately mantra. His playing has always struck me as a unique realization of poetry, prayer, and meditation.

Those familiar with tabla as musical accompaniment will find classical tabla music to be a different kind of experience. In the context of accompaniment (usually with a lead melodic instrument such as sitar, flute, etc.), tabla functions much as drums typically do, to keep time for the main artist and provide ornamentation. Solo tabla music, on the other hand, is more like spoken word or sacred recitation or prayerful chanting. It can be incredibly groovy and emotive, but its primary aesthetic form is linguistic (or phrasal) rather than rhythmic. In this sense, tabla is not very different from the sitar, since melodic instruments in classical Indian music derive from vocal music. The vocal music of raga melody is “song” while the vocal music of tabla is “chant”.

The linguistic and vocal element is critical in playing tabla music. The ability to properly recite the composition determines whether or not it can be played. I have noticed time and time again that if the recitation is clear, the playing will follow with ease. I cannot play what I cannot speak. The practice of recitation also seems to build the relationship between the spoken syllables and the sounds produced on the drum. The language becomes audible.

The course of study and practice for tabla is lifelong. More than this, tabla is impossible to learn without a teacher. The compositional language of the instrument along with its technical elements are not textually recorded and have been preserved through oral tradition. Until recently, tabla music had no written form. Teachers taught their students the compositions they had memorized from their teachers. Through recitation, these compositions are committed to memory and musical form. These forms vary from lineage to lineage, just as the dialects of any language naturally vary by region, but a basic consistency is found across the tradition. Similar to traditional art forms as astrology and medicine, the secrets of tabla music have to be taught or risk being lost. The first transcription system for tabla composition was created by Bhatkande, who wrote the first modern treatise on Indian classical music in the early 20th century.

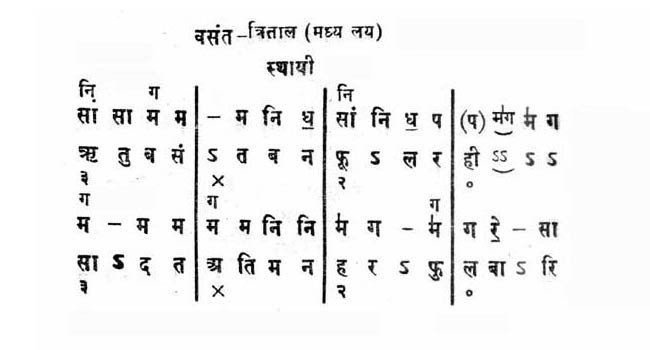

One of Aloke’s unique contributions to tabla music is the creation of a new and complete transcription system. In his books, he transcribes classical compositions showing the beats in the time cycle, the syllabic arrangement, and the syllabic emphases. His work is really a typographical revelation of tabla music and I have come to rely on it in many ways. At times I got ahead of myself and tried to play compositions I had not been taught. I always found these compositions nearly impossible to play, even though I knew the syllables and how to produce them technically.

The way my learning has actually worked is that Aloke teaches me a composition by reciting it himself. Then he asks me to recite and clap. I inevitably make errors in recitation or time keeping and he will say, “Do it again!”. Then he plays it for me and reveals the poetry of the composition. Until the next lesson, my homework is to practice this recitation more than anything else and begin playing the composition. At this point, Aloke has been putting all the emphasis on recitation. He told me in a recent lesson that there is no need to try to play the composition, that is not where the trouble will be, focus on recitation.

This process has interesting similarities to the idea of oral transmission (or rlung) in Tibetan culture. In the Tibetan Buddhist context, students are given the oral transmission of a particular practice by a teacher. This consists of the teacher reciting the practice and associated mantras aloud in Tibetan. The hearing of this is considered the empowerment needed to lawfully begin the practice. When I was learning Tibetan Medicine, Menpa Wangmo placed great emphasis on oral tradition and oral transmission. She recited the Four Tantras of Tibetan Medicine to us in Tibetan, verse by verse, over the course of five years. Once when a student was late to class, she reprimanded the student’s casual attitude which was the true root of the tardiness, reiterating the necessity to receive the oral transmission. This may seem strange in a Western context, but it is not really so strange at all. In fact, embedded within the concept of oral transmission are the subtle laws of education, mastery, and even Enlightenment.

References

[1] Tabla Lessons and Practice by Aloke Dutta

[2] Poetic Drumming by Aloke Dutta

[3] Aloke Dutta transcription example

[3] Scriptless Verse by Aloke Dutta

[4] DigiTabla