Tibetan Moxibustion

On the Tibetan origins of moxibustion and its clinical application, as revealed by Prof. Chögyal Namkhai Norbu.

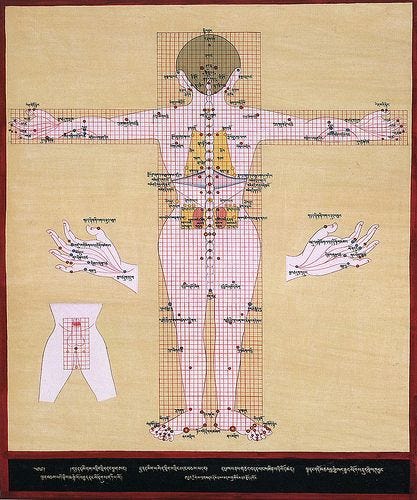

Moxibustion points, Tibetan Medical Thangka, 17th century.

A wide variety of illnesses that are difficult to treat with other therapies can be cured with moxa.

—Prof. Chögyal Namkhai Norbu

The Origins of Moxibustion

According to the research of Prof. Chögyal Namkhai Norbu, moxibustion therapy originated in Tibet over 4,000 years ago. The common historical narrative is that the techniques of acupuncture and moxibustion originated in China, and that the English term moxa is derived from the Japanese term mogusa. However, Norbu (himself a scholar of language and history) asserts that the origin of the term moxa is, in fact, from the Tibetan metsa (me means “fire” and btsa means “focal point”). It is difficult to ascertain the exact line of transmission, but we can make an educated guess to the linguistic and cultural transmission from Tibet to China to Japan.[1] Norbu’s assertion is validated in the Su Wen, the source-text of classical Chinese medicine, which states:

Moxa comes from the north, the highland, where wind, cold and ice reign. . . . The cold that prevails generates illnesses of emptiness that the people cure with moxa.

This passage is quoted by George Soulié de Morant in his tome, Chinese Acupuncture. After presenting this quotation, he adds:

Moxa (jiu), the ideogram for which is formed from the elements “fire-extended",” is said by the Su Wen to have come from the north (Mongolia?).

As his question mark indicates, Soulié de Morant was unsure of the precise area indicated by “north”. I propose that the likely location of the “north” is the Tibetan plateau.

The Tibetan use of moxibustion differs from the Chinese in its theory and practice. Tibet shares its borders with China and Mongolia, and is located at the highest elevation, the “roof of the world”. Tibetan Medicine and Mongolian Medicine are extremely similar (aside from differences in folk traditions). To this point, Tibetans have even included a Mongolian compress therapy known as horme, even retaining the Mongolian terminology in homage to its origins. Therefore, it seems very plausible that the method of moxibustion originated in Tibet. This is also logical when we consider that the methods of needles and moxa originated in response to climatic conditions.

The Su Wen states that stone needles came from the East where people ate fish and salt, giving rise to heat diseases and abscesses while the use of fine needles came from the South “where the sky and earth generate constantly and the yang sun abounds” and the people suffer diseases of spasms and rheumatism. This places moxa in the north and fine needles in the south; heat therapy for cold diseases in the north and cold puncturing therapy for heat diseases in the south.

While moxa may have its origins in Tibet, it has developed significantly in Japan. The use of moxa is so prevalent and sophisticated in Japan that it is licensed separately from acupuncture. In the history of Japanese acupuncture, there have been prominent practitioners (such as Wachi Sugiyama) who chose moxa as their primary clinical modality.

Indications and Contraindictions

Moxibustion is a form of “healing with fire” and thereby restoring the flow of life-energy. Ancient conceptions of circulation most commonly describe the vital force that maintains the health of the body as a fire. The blood is seen as the carrier of the central life-fire throughout the whole body. Asian medical traditions all agree that the spirit resides in the Heart and there is a connection between the Heart, spirit, vital force, and Blood in these systems. We can see why moxibustion was a fundamental therapy for preventing disease and restoring health. Healthy inner heat is the alchemical cornerstone of well-being on all levels.

According to The Oral Instruction Tantra of Tibetan Medicine, moxibustion is indicated for cold, wind, blood, and lymph disorders. It is especially beneficial for indigestion, weakened digestive heat, edema, ascites, reducing tumors, contagious diseases of the throat, empty fever, mental disorders, and loss of consciousness. The Tantra also states that moxibustion is beneficial in alleviating pain, preventing excess wind from arising after empty fever, increasing digestive heat / supporting healthy digestion, reducing abnormal growths (including tumors), healing chronic sores, preventing the spread of malignant tumors, reducing swelling caused by injury / physical trauma, protecting the hollow and solid organs, increasing bodily heat, and restoring clarity to the mind.

In his text, Healing with Fire, Chögyal Namkhai Norbu details the practice of moxibustion and the location of over 300 points alongside a list of indications for each point. In his treatise, Norbu weaves a cohesive narrative drawn from various sources which are meticulously cited: The Oral Instruction Tantra (from the Four Tantras of Tibetan Medicine); two versions of the Sanskrit text purportedly written by Nagarjuna titled Somaraja which was translated into Chinese and subsequently into Tibetan by Vairocana, and a series of lateral back points found in the instructions of Rigdzin Changchub Dorje, Norbu’s root-teacher. Norbu opens with a description of when and how to harvest moxa:

Collect the appropriate herbs for moxa on an auspicious day during any of the three autumn months.

While artemisia is now universally used in moxibustion, Tibetans originally favored a local herb named spra ba (pronounced “trawa”), identified as Leontopodium franchetii. Trawa is a plant in the same genus as edelweiss (Leontopodium alpinum), and its leaves are covered in white hairs. This points to the origins of moxibustion as a local folk therapy, practiced by laymen and shaman alike, in which a variety of local plants were utilized depending on the region.

After discussing the proper preparation of the moxa plant, Norbu continues to describe the indications and contraindications for moxibustion therapy. In summary, moxa is indicated for cold, wind, phlegm, and lymphatic conditions and contraindicated for heat-natured conditions involving blood and bile. The Tibetans present a further domain of contraindication which concerns the proper of timing of moxibustion therapy, as indicated by astrological factors (especially in regards to the lunar cycle). The consideration of “prohibitions” is absent in modern practice, where a full-time work schedule takes pragmatic priority over the role of astrological and spiritual factors in treatment.[2] These astrological factors are sufficiently detailed as to require a lengthy appendix to the text. The resourceful appendix details the location of the “protective energy” (or bla) in the body in relation to various scales of time including the year, days of the lunar month, days of the week, differing periods of the lunar month, and periods of the day. These factors are calculated on the basis of Tibetan astrology and its accompanying 120-year cycle, element, trigram, and animal correspondences.[3] After presenting these detailed indications, Norbu notes that the position of protective energy in relation to the twelve periods of the day is considered more critical than yearly or monthly factors.

Norbu also presents two additional astrological factors for consideration that are drawn from Indian astrology: visti and nāga kulika. Visti is a negative astrological influence that is related to the zodiacal course of planetary movement. When present, external therapies and treatments are contraindicated. The following summarizes the presence of visti in the morning or afternoon, depending on the day of the lunar month:

On the 4th, 11th, 18th, and 25th days of the lunar month, visti is present in the afternoon.

On the 8th, 15th, 22nd, and 29th days of the lunar month, visti is present in the morning.

Nāga kulika refers to a spiritually inauspicious time of day which occurs in hourly patterns depending on the day of the week. Depending on the day of the week, naga kulika can be present anywhere 2-4 times in a single day.

The reality of unfavorable astrological influences impacting treatment outcomes is a worthy consideration. In Western culture, such factors and the calendars they rely upon are foreign systems of knowledge. However, in Indian and Tibetan culture, physicians kept charts and calendars in their clinics so they could quickly check for astrological contraindications before administering treatment. In that cultural context, a physician had the freedom to invite the patient to return for treatment at an opportune time, and treatment itself thus became infused with the energy of ritual practice. Practitioners of acupuncture, East and West, should take heed. If the purpose of treatment is restore the resonance between microcosm and macrocosm, then why would we not take astrological considerations more seriously? We may find our patients respond much better when we consider these environmental influences and therefore take less lightly the role we have as therapists influencing the energy-process of our patients.

Norbu concludes his appendix with the “auspicious mantra for eliminating negative consequences”. He states that the mantra should be recited before performing external therapies in cases when the therapy has to be performed in a time or place that is unfavorable for the spirit of the patient. The presentation of an extensive discussion of contraindications followed by a simple antidote for said contraindications is a characteristic pedagogy in Tibetan medical texts.

Nature of Moxa Points

Concluding the discussion of indications and contraindication, Norbu’s text continues with a discussion of the two types of moxa points: (1) local points and (2) points located by the therapist. Norbu’s description provides some additional qualifiers:

Any painful spot on the body where pressure of the thumb brings relief, any spot on the body where strong pressure of the thumb leaves an imprint, any spot affected by continuous shooting pain, the site of conditions that appear suddenly (such as injuries, cysts, acute swellings).

The first qualifier corresponds exactly to the Chinese concept of ashi points while the second qualifier describes a condition of deficiency. The overall concept of local points is the diagnosis and treatment of an acute condition in the manner of first-aid.

The second category of points located by the therapist are drawn from the Last Tantra of Tibetan Medicine (phyi ma’i rgyud) and medical texts from the Shang Shung civilization. This category includes a total of 500 moxibustion points organized by location: (1) points on the back (2) points on the front and (3) points on the extremities.

This brings us to the fundamental question concerning the nature of points in Tibetan medicine. How does Tibetan medicine define points? Tibetan medicine does not describe points as an energetic convergence on a meridian-like channel. Rather, points are located all over the body without a channel basis. In large areas of the body such as the front and back, the points are displayed in a grid-like fashion, while the extremities see more isolated location. Most points are located in key anatomical zones and at times in a five-pointed constellation spanning the area. Many of the Tibetan moxibustion points coincide directly with Chinese acupuncture points, but many do not. Guariso postulates that “many of the fixed moxa points appear to be located on an energetic structure connecting the internal hollow and solid organs, the senses, and the Wind, Bile, and Phlegm energies that govern all physiological functions”.

His description is nearly identical to the description of marma points in Suśruta’s Samhita, a classical Ayurvedic text on point-based therapies that was influential on Tibetan medical thinking. According to Suśruta, marma points represent the intersection of dosa and dhatu, and therefore are placed where the vitality of the body can be directly influenced. Therefore, it appears that the Tibetan system of points draws at least theoretically from the Ayurvedic tradition. Further evidence of this can be seen is the fundamentally doshic nature of the indications for treatment and the identical name of some moxa points with the sub-doshas, such as “Fire-Accompanying Wind Point”. This shows that the Tibetan system of moxibustion conceives of its therapeutics in resonance with Ayurvedic thinking. Notably, I am not aware of a comparably elaborate point-based therapy in Ayurvedic medicine, which typically enumerates only 107 classical points with some lineage variations of this number.

Four Methods of Treatment

Returning to Norbu’s treatise, having established the basis of point selection, he describes four methods of moxibustion:

(1) cauterizing (btso ba)

(2) burning (sreg pa)

(3) heating (bsro ba)

(4) threatening (sdig pa)

The first method of cauterization is the primary practice described in the Mawangdui manuscripts. It is likely the first form of moxibustion practice (or the larger tradition of moxa-cautery). Cauterization is indicated for serious physical illness which was more common in the past, especially in the nomadic culture of Tibet. Individuals were more vulnerable to diseases caused by weather conditions such as intense cold or heat, trauma from farming and animal husbandry, etc. Norbu states that cauterization is best for patients who are critically ill, including conditions such as cysts and tumors. A large moxa cone is used and while the cone is burning, the practitioner blows on the cone until it is completely burned. Norbu describes that after the cone has burned, “with the sound tsak, a small piece of seared skin cracks away”.[4] This is also known as “scarring moxibustion” and has a history of practice in the Chinese medical tradition. Cauterization can also be performed with metal rods, as in the agni karma of Āyurveda and the metal rod therapy of Tibetan medicine.

The second method of burning is indicated for cold-natured phlegm conditions, lymphatic disorders, and heart-wind imbalance[5]. This method is performed similarly to cauterization but with less intensity. Norbu cites the use of small cones in Japan as having a mild effect even when performed regularly. He may be referring to the practice of rice-grain moxa in which a thread-like moxa is placed on the skin and burned all the way down. The small size of thread results in a mild effect that is tolerable to the patient. However, it is notable that some degree of heat is indicated here in order to dissolve phlegm, move lymph, and invigorate the spirit––yet in this method, the skin is not necessarily burned as it is in the cauterization method.

The third method of heating is indicated for severe wind disorders, microorganism conditions,[6] and channel obstruction (including urine retention, edema, and blood stasis). In this method, moxa cones are burned directly on the points five, seven, or possibly more times. Norbu indicates that if the illness is not serious, then the point should be deeply warmed with seven or more moxa cones. This is perhaps the most common form of moxibustion therapy in modern practice. It corresponds to the Japanese practice of chinestskyu and is the method practiced in Worsley Classical Five-Element Acupuncture as well.

The fourth method of threatening is indicated for children, elderly, and pregnant women, regardless of the presenting condition. Norbu describes the method:

. . . the heat from the moxa should be applied to a degree sufficient only to generate a fear of the heat or the feeling of being threatened by the heat. This kind of application is repeated as appropriate, without placing the source of heat directly on the point.

Norbu is referring to the application of moxa cones on an intervening medium, commonly a thin slice of ginger or garlic (chosen in respect to the patient’s constitution and condition). This is technically an indirect form of moxibustion where there is no possibility of burning the skin and heat is moderated by the medium.

In conclusion of the methods of moxibustion, Norbu notes that even in less severe illnesses indicated for cauterization and burning, the gentler methods of heating and threatening methods “can be applied repeatedly with great effect”.

Post-Treatment Guidelines

In the penultimate section of his treatise, Norbu describes post-treatment guidelines for the patient, following moxibustion therapy. Following cauterization or burning, the practitioner should place their thumb directly on the point. After this, the patient should stand up and walk a few steps. Norbu states that this “brings the condition of the body back to normal”. General aftercare advice includes avoiding the drinking of any liquids, especially cold water. The patient should be advised to avoid the following:

acidic foods or drinks for seven days (spoiled food, fermented food, yogurt, buttermilk, beer, alcohol, etc.)

exposure to cold

sweating from strenuous activities

sleeping during the daytime

Benefits of Moxibustion

Norbu concludes his text on moxibustion with a description of the benefits of moxa in list form:

clears obstructions within nerves and blood vessels

relieves pain related to illnesses

alleviated wind disorders that affect various parts of the body

improves poor digestion

cures illnesses such as epigastric disorders and tumors

potentially arrests the development of cysts and noxious flesh growths, heals chronic wounds

reduces swellings of various kinds

removes and dries up lymph

protects the functioning of the solid and hollow organs

increases bodily heat

induces mental clarity

Moxibustion in Chinese, Japanese, and Five-Element Acupuncture

Norbu’s presentation of the Tibetan moxibustion tradition is the most exhaustive in print. It details an indigenous tradition that evolved alongside neighboring traditions, forming a rarely-achieved theoretical and clinical synthesis. While early moxibustion practices were folk healing practices, Norbu presents a therapeutic system of points, point measurement and location, therapeutic indications, contraindications, and methods of treatment.

In Chinese acupuncture traditions, moxibustion is often used in tandem with needling approaches. In Chinese medicine, moxibustion is contraindicated for excess / heat patterns but indicated for deficiency / cold patterns. In Japanese acupuncture, moxibustion is used more frequently and seen as having a broader therapeutic effect that is not achievable through needling alone. Moxa is considered to boost the immune system, increase circulation, stop pain, warm the channels, dispel damp, and calm the spirit. Acupuncture masters of the past famously recommended burning moxa regularly on ST-36 for prevention of disease.

In the classical Five-Element tradition, moxa is only contraindicated in cases of high blood pressure, but is otherwise burned directly on points and followed by needle. The burning of moxa is considered to have a vitalizing and nourishing effect. While moxa is considered tonifying in general, it can also be used with the intention of tonification or sedation, according to the overall treatment strategy. For tonification, an odd number of cones should be burned, and allowed to burn on its own. For sedation, an even number of cones should be burned and the practitioner can either blow on the moxa or gently fan it. Why the even and odd numbers? Odd numbers are yang in nature as they are still “growing” toward something. Even numbers are yin in nature as they are balanced as they are. Moxa also is a powerful disinfectant for the skin and the air in which it is burned. Its cleansing effect may be another reason why it is burned before needling in times predating the use of ethyl alcohol. Moxa has such a multitude of uses but its primary effect in my understanding is its ability to invite and rejuvenate the spirit.

Notes

[1] There is evidence of cross-cultural transmission between Tibet and Japan via Zen Buddhism. See Sam Van Schaik’s Tibetan Zen.

[2] An interesting discussion of “prohibitions” is found in the Japanese text, The Yellow Emperor’s Toad Canon. This text corresponds to Tibetan medical ideas of appropriate timing for treatment and the regard a physician must give to the “protective energy” (or “spirit”) of the patient.

[3] The elemental nature of the year uses the framework of Chinese five-element theory: Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, Water. The trigram and animal correspondences are also drawn from Chinese astrology.

[4] The technique of blowing on the moxa cone is known in Japanese practice as a “sedating” technique, where strength of stimulus = sedation and minimality of stimulus = tonification.

[5] Heart-Wind imbalance is known in Tibetan as snying rlung. In the language of Ayurveda, it corresponds to an imbalance of prāna vāyu. Tibetan medical texts describe heart-wind imbalance as a Wind disorder that also imbalances the Earth element. Symptoms include trembling, a sensation as if the chest were filled with air, yawning, mental confusion and instability, senseless speech, dizziness, and insomnia. In TCM, heart-wind disorder can be understood as a form of heart-yin deficiency. In Western medical terms, heart-wind imbalance can be seen as a form of depression.

[6] The Tibetan classification of microorganism and parasitic conditions is extensive and could be seen in parallel to the classical Chinese classification of gu syndromes, as presented in the work of Heiner Fruehauf.