MDMA Papers: Mandible Wheel

On the Phenomenology of Jaw Clenching, Wish Fulfillment, and the Talking Cure

Preface

This essay is part of a larger collection titled MDMA Papers, which explores the pharmacology and therapeutics of MDMA. “Mandible Wheel” follows in Freud’s footsteps by linking psychopharmacology and psychoanalysis. In this essay, I argue that jaw clenching is a symptom of repression that is therapeutically amplified by MDMA. On this basis, I propose a psychoanalytic mechanism and framework for MDMA-assisted therapy.

“Mandible Wheel” explores the therapeutic phenomenology of MDMA within a psychoanalytic and Chinese medical framework. The first part of the essay presents jaw clenching as a psychosomatic phenomenon of repression and its abreaction. I argue that our symptoms are cathartic mechanisms rather than mere side effects.

The second part of the essay examines a physiological perspective of jaw clenching through the anatomy of the Stomach meridian. I discuss the location and significance of ST-6, and consider jaw clenching a phenomenon related to Stomach Qi and the “digestion” of repressed content.

The third part of the essay explores the psychosomatic importance of the jaw by analyzing its correspondence with Hexagram 27 of the Yijing, the phenomenology of nourishment, and the Chinese meridian clock.

The conclusion of the essay examines the jaw and mouth from a Yogic perspective as a vital region of conductivity where tension accumulates. I posit the jaw as the organ of the speaking body and, therefore, the mechanism of the talking cure.

In terms of style, this essay oscillates between expository prose and poetic verse.

I. The Psychosomatics of Repression

MDMA is a psychosomatic medicine—it operates on psyche and soma. The somatic effects of MDMA are thus equally psychic. What is psychosomatic is also psychedelic. That is to say, MDMA amplifies psychic content—material that is not only in the mind but held deeply within the body.

One notable effect of MDMA is jaw clenching. A biochemical explanation for the symptom of jaw clenching is that MDMA is a stimulant, which is another way of saying that clenching is a phenomenon of stimulus. However, this explanation provides us with no further insight. If we accept that MDMA is a psychosomatic medicine, then none of its effects can be reduced to a purely physical explanation. From a psychosomatic perspective, so-called “side effects” are revealed as therapeutic mechanisms, or what psychoanalysis calls abreactions. In their landmark publication, Studies in Hysteria, Breuer and Freud define abreaction as a cathartic release of repressed emotion:

The injured person's reaction to the trauma only exercises a completely ‘cathartic’ effect if it is an adequate reaction—as, for instance, revenge. But language serves as a substitute for action; by its help, an affect can be ‘abreacted’ almost as effectively. In other cases speaking is itself the adequate reflex, when, for instance, it is a lamentation or giving utterance to a tormenting secret, e.g. a confession. If there is no such reaction, whether in deeds or words, or in the mildest cases in tears, any recollection of the event retains its affective lone to begin with.1

If we understand the side-effect of jaw clenching as an abreaction, then we recognize catharsis as the primary therapeutic mechanism of MDMA (and of psychedelic therapy in general). When we abreact, we recover and retrace the shocks that keep our vital force. We speak our dreams, chew on our reflections, and metabolize our memories. Abreaction is the re-emergence of vital intelligence where it was made unconscious.

Jaw clenching is a psychopathology common to everyday life.2 Jaw clenching is one of the more obvious psychosomatic conditions—its etiology is stress, specifically the stress of repression. In The Ego and the Id, Freud elucidates the relationship between repression and the unconscious:

We recognize that the unconscious does not coincide with the repressed; it is still true that all that is repressed is unconscious, but not all that is unconscious is repressed.3

The relationship between the repressed unconscious and the unconscious proper is the relationship between constitution and condition, or the structure and the symptom. When we cleanse repressed phenomena from the surface of the psyche, its deep structure self-emerges. Thus, cure unfolds from the unconscious proper—from the depth to the periphery, from above to below, and from present to past—while repression moves from the surface to the center, from below to above, and from past to present.

Trauma is a blocked affect.

Affection is libido,

and libido is a vital force.

The blocked affect is where our élan

loses vital contact with reality.

We relive our trauma by coming alive again,

purging to purify in dramatic release.

Therefore, healing is rebirth,

a resurrection of the vital force.

The psyche is a vital impetus that drives

the enlightenment of the whole body.

“Sometimes the frustrated wishes are neither possessive nor libidinal drives,

but rather drives toward self-realization”.4

At night, we chew and attempt to digest psychic content.

What we fail to digest becomes the substance of nightmares,

haunting us from near and afar.

Repression is indigestion,

a psychic artifact

that never ripens but only rots,

its fermentation a poisonous heat

that cooks our vital essences.

II. An Anatomy and Physiology of Jaw Clenching

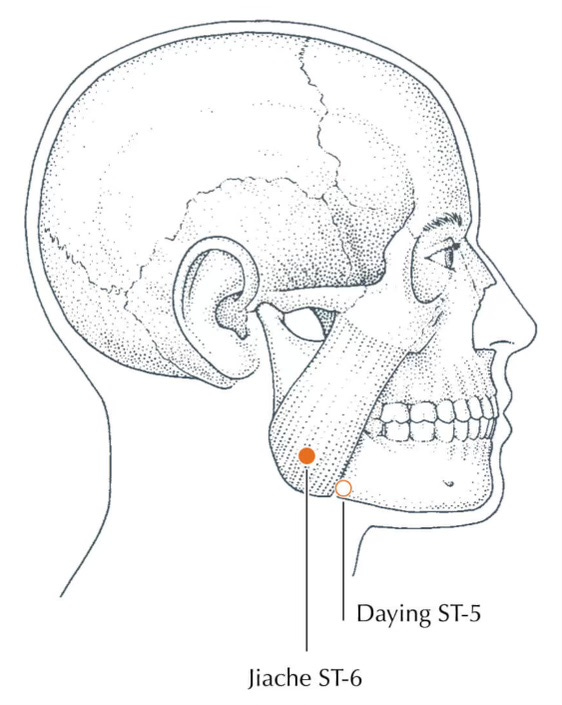

“Anatomy is destiny”.5 In acupuncture anatomy, the Stomach meridian begins its flow inferior to the eye, between the infraorbital ridge and the eyeball (ST-1 “Receive Tears”). From here, the meridian flows downward into a depression in the infraorbital foramen (ST-2 “Four Whites”), continues to descend into the cheek, level with the lower border of the ala nasi (ST-3 “Great Cheekbone”), and down to the level of the lips, in the continuation of the nasolabial groove (ST-4 “Earth Granary”). From here, the Stomach meridian descends to the jaw, at the anterior border of the masseter muscle (ST-5 “Great Welcome”), and then flows upward into the prominence of the masseter muscle (ST-6 “Mandible Wheel”).

ST-6 is aptly named “Mandible Wheel” (jiáchē), as it is directly located in the mandible, but we will see that this name also has esoteric connotations. In addition to being a point on the Stomach meridian, ST-6 is also classified by Sun Si-Miao as one of the thirteen ghost points—points used to treat possession syndromes.6 In the ghost-point schema, ST-6 is given the alternate name “Guichang”, meaning “Ghost Bed”.

“Mandible Wheel” is J.R. Worsley’s translation of the Chinese jiáchē.7 The term jia means “cheek; jaw, jawbone; side, to press together from both sides; to assist, to support”. The term che means “cart, chariot, vehicle; jawbone; to ride, to turn (oneself)”. A “mandible wheel” is where the spokes of the psyche turn, where we initiate a digestive cycle that nourishes us in turn. Therefore, MDMA is a circulatio of healing—it moves the wheels of repression and steers our life.

In Chinese medicine, the Heart is described as the spiritual throne of the vital force. The Heart corresponds to the fire element, the period of solar noon, and the zodiac animal of the horse. The horse is an ancient symbol of the libido. A horse roams free in the wild, independent and related. The horse chews the day away and is thus an image of the jaw. As we see, one of the meanings of jia is a chariot, a wheeled carriage traditionally driven by horses. When we chew, we press the teeth together and amalgamate the food of life. Therefore, the Mandible Wheel is an image of libidinal freedom, the recovery of a balanced vehicle, a fusion of sides that powers the whole.

Peter Deadman comments that ST-6 is “an important point in treatment of a wide range of local disorders affecting the jaw, including inability to chew, inability to open the mouth after windstroke,8 lockjaw, and tension, pain or paralysis of the jaw”.9 Deadman adds that he is unable to find a rationale for the classification of ST-6 as a ghost point because ghost points were used “to treat mania and epilepsy” and that “there are no indications of this kind listed for the point”.10 But points do not exist for symptoms. Points are the language of the speaking body. Points are signifiers that articulate a line of resonance between constitution and condition.

We need to understand windstroke, mania, and epilepsy as possession syndromes. Sun Si-Miao’s classification of ST-6 as a ghost point indicates its relevance for possession syndromes in general, not only for palliating symptoms from windstroke.

Possession syndromes are pathologies of Stomach Qi. The Chinese term for Stomach is wei (胃), a character “drawn as a container full of grains and flesh . . . [it] represents the vitality of nourishment that can penetrate where it is needed”.11 The Stomach is the cauldron of life, where we consume the edible, and gather strength to move in the carriages of our destiny.

III. The Phenomenology of Nourishment

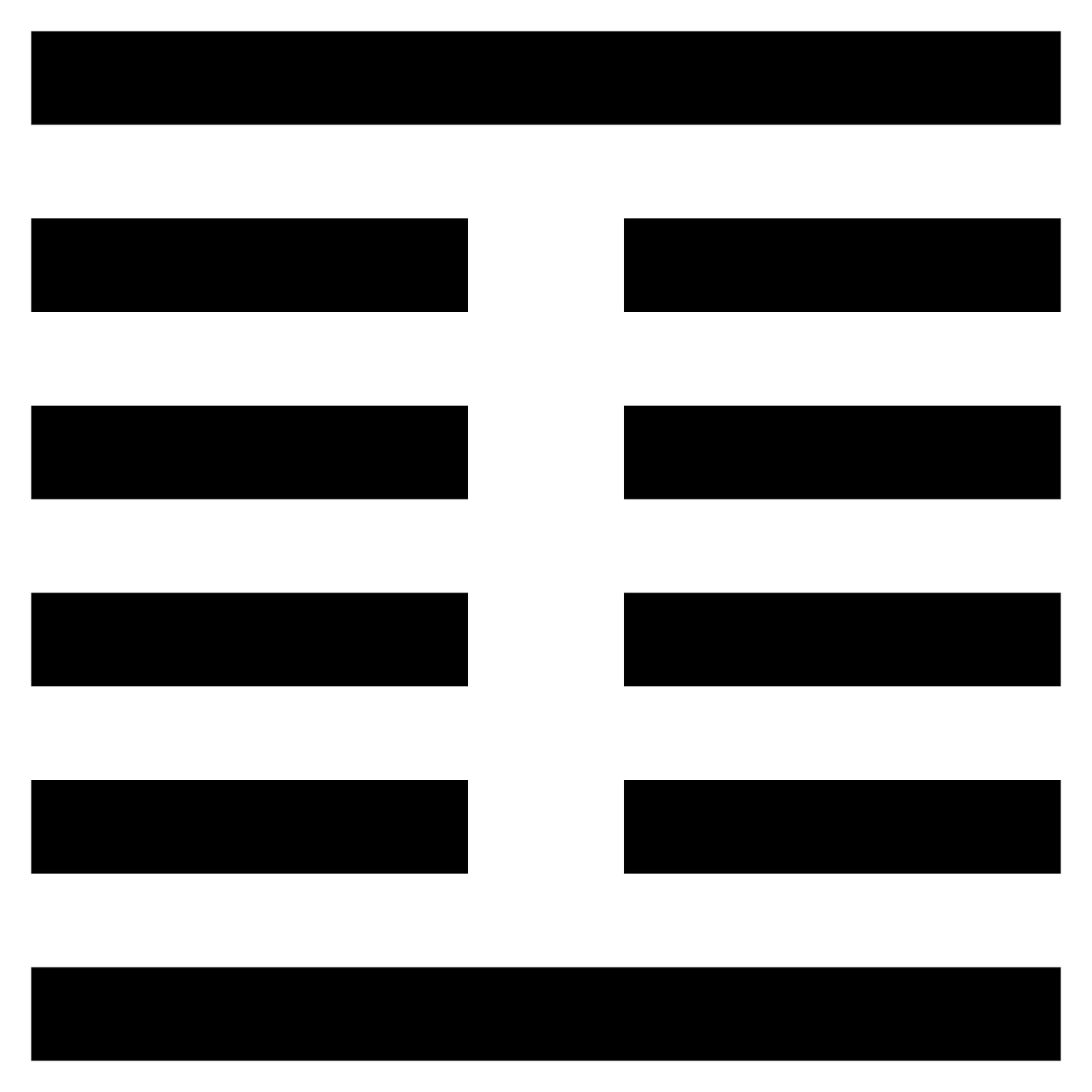

Hexagram 27, Nourishing

ST-6 corresponds to Hexagram 27 of the Yijing—Yi (Nourishing). Wilhelm translates Yi as “The Corner of the Mouth (Providing Nourishment)” and Blofeld translates it as “Nourishment (literally Jaws)”. The jaw and mouth are ancient images of nourishment that occur throughout the Yijing. Commenting on Hexagram 27 (Yi), Huang writes:

When we eat, the upper jaw holds still; only the lower jaw moves up and down. The subject of the first three lines is to nourish oneself; that of the next three lines is to nourish others.12

This hexagram is composed of two solid lines (at the top and bottom) and all yielding lines in the center. Hexagram 27 thus gives the image of an open mouth. When we dissect the hexagram into two trigrams, the upper and lower three lines each form the upper and lower jaw. Huang interprets the lower three lines (and lower jaw) as an image of nourishing oneself and the upper three lines (and upper jaw) as an image of nourishing others. He comments that the nourishment of this hexagram has less to do with “the act of eating and drinking, and more with the wisdom of nourishing oneself as well as other people”.13 Thus, the mouth and jaw are seen as images of relationship.

To nourish oneself is to nurture inner “virtue”; to nourish others is to feed them with your presence. The Commentary on the Symbol states:

Thunder beneath Mountain

An image of Nourishing.

In correspondence with this,

The superior person is careful of his words

And moderate in eating and drinking.14

Huang writes that “the ancient sages proclaimed that nourishing and nurturing were not a matter reserved for the family but concerned society as a whole . . . Compared with nourishing one’s virtue, nourishing one’s body was secondary. Thus, the sages were cautious of words and moderate in diet and provided nourishment and nurturing to the people”.15

We can thus understand the action of MDMA within the archetypal phenomenology of “nourishment”. MDMA is a mandible wheel of nourishment—fostering an ecological connection to self and other, to body and world.

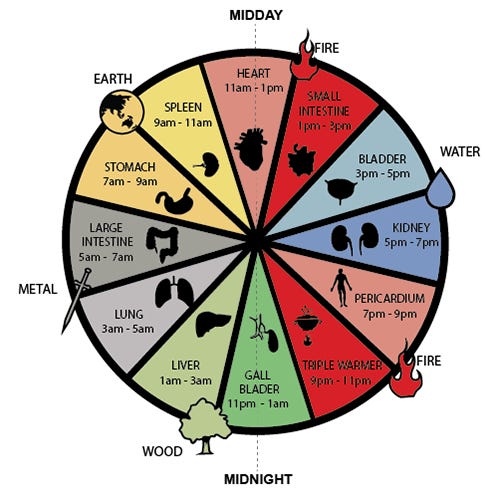

Timing Nourishment: Clock Opposites and Identical Qi

The connection between nourishment and relationship becomes evident when we consider that the Stomach and Pericardium are “clock opposites”. In the context of the Chinese meridian clock, the Stomach corresponds to the hours of 7-9 am, and the Pericardium corresponds to the hours of 7-9 pm. Thus, the Stomach and Pericardium exist in a Qi dynamic, on opposite sides of the daily rhythm. In the morning, we extract the essence of food and drink; in the evening, we make love.

During the MDMA experience, we can digest significant portions of psychic material in a short span of time. The locus of psychical causality lives in a prayer, as a “totally lived interiorization”16 that operates beyond and prior to time. Minkowski writes:

But this interiorization does not bring me face to face with myself. It is, as we have said already, neither reverie nor the free play of the imagination. Quite to the contrary, in springing up from the depths of my being, it goes beyond the universe. It is in this sense a totally lived extrospection. In a flash of the eye my glance now passes through the universe, takes it in completely and goes beyond it . . . we could say that prayer puts us in the presence of God; of a God, however, whose activity ought to be manifest in the world in which we live.17

“Ecstasy” literally means to “stand outside oneself”.18 But this “standing outside” is simultaneously a “touching within”, an enstasis.

MDMA gives us a digestive capacity that is not limited by time. We cook time in the navel of our living. We vitalize the psyche in the soma. We pray in the fire for the fulfillment of our wishes. Digestion begins in the mouth. By chewing, we re-metabolize what we repressed. MDMA is a prayer of changes, a sacrament of universal sacrifice, a sacramental communion with the vital principle of life.

Chronic jaw clenching is a psychopathology caused by repression. The location of ST-6 in the mandible reveals repression as an indigestion, and health as a phenomenon of Stomach Qi. In Chinese medicine, the Stomach is viewed as an alchemical cauldron, the “official in charge of the rotting and ripening of food and drink”. The Stomach is our digestive container, the vessel in which we cook the raw materials of life into vital essences, nourishing our body, mind, and spirit.

From this, we can conclude that MDMA amplifies the Stomach Qi. MDMA kindles an inner flame, a crucible in which we place our traumas and memories, our dreams and reflections, our betrayals and rejections, our hopes and expectations, our pasts and futures. We are the dragon and its treasure—a wish-fulfilling jewel guarded in our bodies, loathsome jaws made edible in a mandible wheel of time.

IV. Unlocking the Jaw: Wish-Fulfillment and the Talking Cure

The jaw and mouth are an erogenous region—zones where the vital force naturally flows, and also where it contracts. In describing an oral phase of development, Freud was emphasizing the mouth as an organ of relatedness—the place where we not only sense but receive nourishment from the Mother. Adi Da describes the functional blocks that arise in the mouth and jaw:

The region of the mouth and jaw is an area of chronic tension for many people. Tension anywhere in the body is a sign that the flow of life-force is obstructed there. The “locks” on the life-force that we feel in the body are signs of reaction, mental, emotional, and physical, to the dilemma that bodily existence itself represents to us.19

Jaw tension is an energetic lock of the life-force on a fundamental level. Jaw stress reflects the tension of conditionality and the feeling of mortality. When we react, we contract the life-force. And all contractions of the life-force are built on the root-contraction of the lower abdomen, which Adi Da calls “vital shock”.20 This is why “external therapeutic approaches to relieving tension are not sufficient”.21 The root of our stress is spiritual, and it creates libidinal tension in the jaw.

Adi Da comments on jaw stress as a physiological block that contracts the nervous system:

The unnatural tension in the jaw obstructs (1) the natural flow of Bio-Energy and cerebrospinal fluid between the brain and spinal cord, and (2) the flow of blood between the head and the rest of the body. Thus, the tension that begins at the jaw is extended to the entire nervous system.22

Chronic jaw clenching creates secondary tensions in the head and neck, and contracts the vitality of the throat. With blocks in the upper burner,23 we struggle to receive and transform the qi of Heaven, which descends into the head, face, throat, and neck, and roots in the lower abdomen. Where we are locked, we lose the integrity of our structure and function. We are no longer placed in space or time, and we lack a gravitational center for our vitality to locus in.

In the traditions of Yoga and Qigong, the posture and conductivity of the mouth are given significance. The breath is initiated through the nose with the mouth closed, and the tip of the tongue should rest naturally at the roof of the mouth, behind the front teeth. Adi Da explains:

In the natural posture of the area of the mouth, the lips are closed, the lower and upper teeth and relaxed and slightly separated, and the tip of the tongue lightly touches the roof of the mouth. When the mouth is thus relaxed and closed, you can breathe easily and naturally through the nose. You can relieve dental stress by reestablishing this natural alignment of the lower and upper jaws.24

The conductivity of the mouth and jaw is central to life. “The relaxed jaw is a natural indication of the regenerative yoga of the body, a sign that the individual is responsible for the processes of the body and awake and relaxed as the body”.25 We can consciously relax the jaw muscles through intentional yawning and through tensing/releasing the jaw muscles. The traditional practice of gagging opens the flow of energy between the spine, neck, and brain. In Ayurvedic practice, a metal tongue scraper (copper or silver) is used for this purpose. Adi Da comments that “gagging also stimulates the digestive processes. Practiced first thing in the morning, it awakens the nervous system from the dormant, drowsy condition that tends to persist after sleep”.26

The Sacrament of Universal Sacrifice

Food is a sacrament, and eating is alchemical. “The taking of food is very important, not just because it is necessary for survival from the mechanical, biological point of view, but because it is a form of meditation. It is a sacrament, literally, and the term ‘sacrament’ symbolically describes the taking of food. It is the taking of God’s Body; it is the taking of Energy, the Force of Reality . . . You must perform alchemy in the mouth and the stomach”.27

Food is an image of the prima materia. The alchemical act is a sacrificial act. When we chew, we transform solid into liquid. This is why the medical traditions have long emphasized that digestion begins in the mouth. In other words, “the mouth is the conscious point of ingestion, not the stomach”.28 Adi Da describes eating as a sacrificial act in which the natural posture of the mouth is temporarily broken:

There is an old principle that you should chew your food many times, breaking it down into a liquid state before swallowing. This practice of eating slowly and carefully is not only for the sake of the stomach and the digestive system. The principal reason for conscious chewing is that the tongue in the aperture of the mouth, is a very important point in the circuit of the Life-Current of our living being.

Ordinarily the tongue should quite naturally touch the roof of the mouth just behind the upper front teeth. When the mouth is open and the tongue is dropped down, you have broken the circuit that conducts the manifest Light or Life-Energy of the cosmos and that makes you intelligent. But when you take solid food, you must bring down the tongue from the roof of your mouth. In other words, when eating you necessarily permit the conversion of solid food temporarily to replace the direct ingestion, through the breath, of the universal Life-Energy and the conducting of that Energy to the whole body from the nose and eyes via the tongue, mouth, and throat.

. . . Even speaking requires lifting the tongue from the roof of the mouth. So, if you are gossiping and speaking craziness and indulging negativity in speech, you are not eating, you are not being sustained . . . Speech should sustain you”.29

Through the mouth, we open to receive food for the body, mind, and spirit.

Our lips articulate the subtle thoughts given voice in the throat.

To eat and to speak.

To consume and to manifest.

The wheel of speech

a spoken phenomenon—

to mouth our prayers

and speak our intentions

into existence.

The tongue is the fruit of the Heart;

the jaw is the mechanism of the talking cure.

We speak our repressed thoughts

and give sound to the images of our dreams.

We voice the unheard

and recognize the real.

In speech,

the jaw unlocks,

and the mandible wheel

moves in motion,

powering our vital contact

with the real.

We find our voice from a place of nourishment

when we are Mothered again by life itself.

Vital shock closes the jaws of life

and leaves the mouth gaping.

We are hungry ghosts

whose unfulfilled wishes

gnaw at the seat of life.

The oral phase of development

is not only constituted by breastfeeding—

it also leaves infancy

to grow in mind and spirit.

In our second birth,

the mouth and jaw are born again

from shock.

Our spirit is reigned and wheeling.

We no longer seek an edible deity,

in tongue or cheek,

but teethe on vital currents.

The lips are the fruit of the Spleen,

a cathexis of the jaw

at the breast of life.

When we breathe in

the food of life

with an open heart

and porous body,

we no longer seek

with pouting lips.

We live in relationship

without otherness,

speaking and loving

in a continuous kiss.

The speaking body becomes

the jouissance of the real,

as we awaken to our dreams

and follow our desires.

The secret of the speaking body

is the letter of love.

To speak of love

is ecstatic.

To speak of love

is speaking as love.

To speak

is to enunciate in ecstasy

the locus mysterium of the real.

Breuer, J., Freud, S. (1893). On the Psychical Mechanism of Hysterical Phenomena in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume II (1893-1895): Studies on Hysteria, 1-17.

Western medicine classifies the pathologies caused by jaw clenching as “temporomandibular joint dysfunction” (TMD, or TMJ Syndrome). TMD is caused by chronic jaw clenching (typically at night) and may be accompanied by teeth grinding (bruxism). Chronic jaw clenching can cause symptoms including jaw pain, headaches, neck and shoulder pain, tooth pain, difficulty chewing, and/or joint locking.

Freud, S. (1923). The Ego and the Id (p. 18) in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XIX (1923-1925): The Ego and the Id and Other Works (J. Strachey, Trans.), 1-66.

Ellenberger, H. (1970). The Discovery of the Unconscious: The History and Evolution of Dynamic Psychiatry (p. 27). Basic Books.

Freud, S. (1912). On the universal tendency to debasement in the sphere of love (contributions to the psychology of love II, J. Strachey, Trans.). In The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud. The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-analysis.

See Pandit, N. (2024). Spirits of the Unconscious: Possession and Resurrection in Acupuncture Therapeutics [Master’s Thesis, Middle Way Acupuncture Institute]. Somaraja Press.

See Worsley, J. B., Worsley, J. R. (2024). Worsley Classical Five-Element Acupuncture, Vol. I: Meridians and Points (5th ed.). Worsley, Inc.

In Chinese medicine, “windstroke” classifies a range of nervous system pathologies that feature sudden paralysis, including stroke and epilepsy. Strokes and epileptic seizures were traditionally viewed as possession syndromes because the person suddenly experiences a loss of sensorimotor function as if they were “seized” by a demonic force. These conditions can also impair memory and other forms of “vital contact with reality”. Thus, we can group windstroke, epilepsy, dementia, schizophrenia, and autism within the phenomenology of possession syndromes.

Deadman, P., Al-Khafaji, M., & Baker, K. (2016). A Manual of Acupuncture (p. 134). Eastland Press.

Ibid.

Kaatz, D. (2005). Characters of Wisdom: Taoist tales of the acupuncture points (p. 321). The Petite Bergerie Press.

Huang, A. (2010). The Complete I Ching (p. 235). Inner Traditions.

Ibid.

Ibid., 236.

Ibid., 237.

Minkowski, E. (2019). Lived Time: Phenomenological and Psychopathological Studies (N. Netzel, Trans., p. 107). Northwestern University Press. Original work published 1933. For Lacan’s review of Minkowski’s text, see Sur l’ouvrage de E. Minkowski, Le temps vécu (1935).

Ibid.

In the “dynamic psychiatry” of nineteenth-century Europe, “ecstasis” was described as a symptom of hysteria and interpreted as a loss of vital contact with reality.

John, B. [Adi Da Samraj] (1978). The Eating Gorilla Comes in Peace (pp. 417-418). Dawn Horse Press.

See Samraj, A. D. (2004). “Vital Shock” (pp. 163-197). In My Bright Word (2004). Dawn Horse Press.

John, B. [Adi Da Samraj] (1978). The Eating Gorilla Comes in Peace (pp. 417-418). Dawn Horse Press.

Ibid., 418.

In Chinese medical anatomy, the torso is divided into three “burning spaces” (jiao). The upper burner spans from the head to the heart.

John, B. [Adi Da Samraj] (1978). The Eating Gorilla Comes in Peace (p. 419). Dawn Horse Press.

Ibid.

Ibid., 421-422.

Ibid., 234.

Ibid., 235.

Ibid., 234-236.

References

Breuer, J., Freud, S. (1893). On the Psychical Mechanism of Hysterical Phenomena in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume II (1893-1895): Studies on Hysteria.

Deadman, P., Al-Khafaji, M., & Baker, K. (2016). A Manual of Acupuncture. Eastland Press.

Ellenberger, H. (1970). The Discovery of the Unconscious: The History and Evolution of Dynamic Psychiatry. Basic Books.

Freud, S. (1912). On the universal tendency to debasement in the sphere of love (contributions to the psychology of love II, J. Strachey, Trans.). In The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud. The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-analysis.

Freud, S. (1923). The Ego and the Id in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XIX (1923-1925): The Ego and the Id and Other Works (J. Strachey, Trans.).

Huang, A. (2010). The Complete I Ching. Inner Traditions.

John, B. [Adi Da Samraj] (1978). The Eating Gorilla Comes in Peace. Dawn Horse Press.

Lacan, J. (1998). The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book XX: Encore 1972-1973. W.W. Norton and Company. Original work published 1975.

Kaatz, D. (2005). Characters of Wisdom: Taoist tales of the acupuncture points (p. 321). The Petite Bergerie Press.

Minkowski, E. (2019). Lived Time: Phenomenological and Psychopathological Studies (N. Netzel, Trans.). Northwestern University Press. Original work published 1933.

Pandit, N. (2024). Spirits of the Unconscious: Possession and Resurrection in Acupuncture Therapeutics [Master’s Thesis, Middle Way Acupuncture Institute]. Somaraja Press.

Samraj, A. D. (2004). My Bright Word. Dawn Horse Press.

Worsley, J. B., Worsley, J. R. (2024). Worsley Classical Five-Element Acupuncture, Vol. I: Meridians and Points (5th ed.). Worsley, Inc.