Preface

Jacques Lacan (1901-1981) was a Parisian physician, psychiatrist, and psychoanalyst. Radical, rebellious, and heroic, Lacan revolutionized the theory, practice, and ethic of psychoanalysis in twentieth-century France. Described as “the most controversial psychoanalyst since Freud” and “the Picasso of psychoanalysis”, Lacan evoked a fresh interpretation of psychoanalysis inspired by the artistic milieu of French surrealism and its literary counterparts.1

Lacan described his project as a “return to Freud” and thus to the modern origin of the psychoanalytic tradition. However, Lacan also evolved psychoanalysis beyond the Freudian conception with his explorations of French phenomenology, linguistic structuralism, mathematical topology, and aspects of Eastern philosophy.

Present are, from left and standing: Jacques Lacan, Cécile Éluard, Pierre Reverdy, Louise Leiris, Pablo Picasso, Zanie de Campan, Valentine Hugo, Simone de Beauvoir and Brassaï (to whom this photo is credited). From left and sitting are: Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, Jean Aubier and Michel Leiris.

In what follows, I offer a Human Design analysis of Jacques Lacan, with the two-fold intention of illustrating the psychoanalytic application of Human Design and how “the style is the man himself”. The examination that follows is by no means exhaustive, but functions as a sketch of Lacan, told through the language of Human Design. For those unfamiliar with Lacan, I offer an introduction to the man and his teachings.

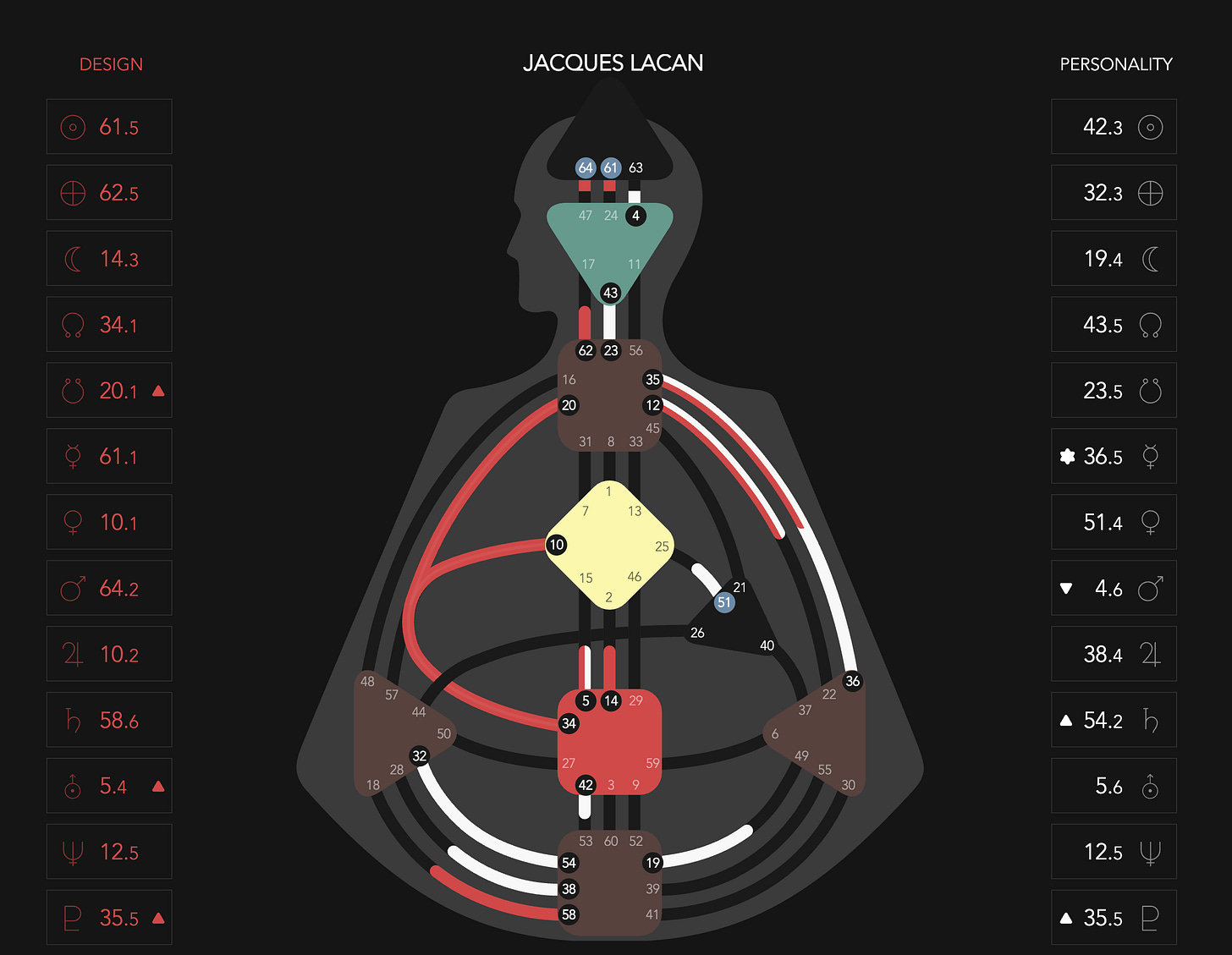

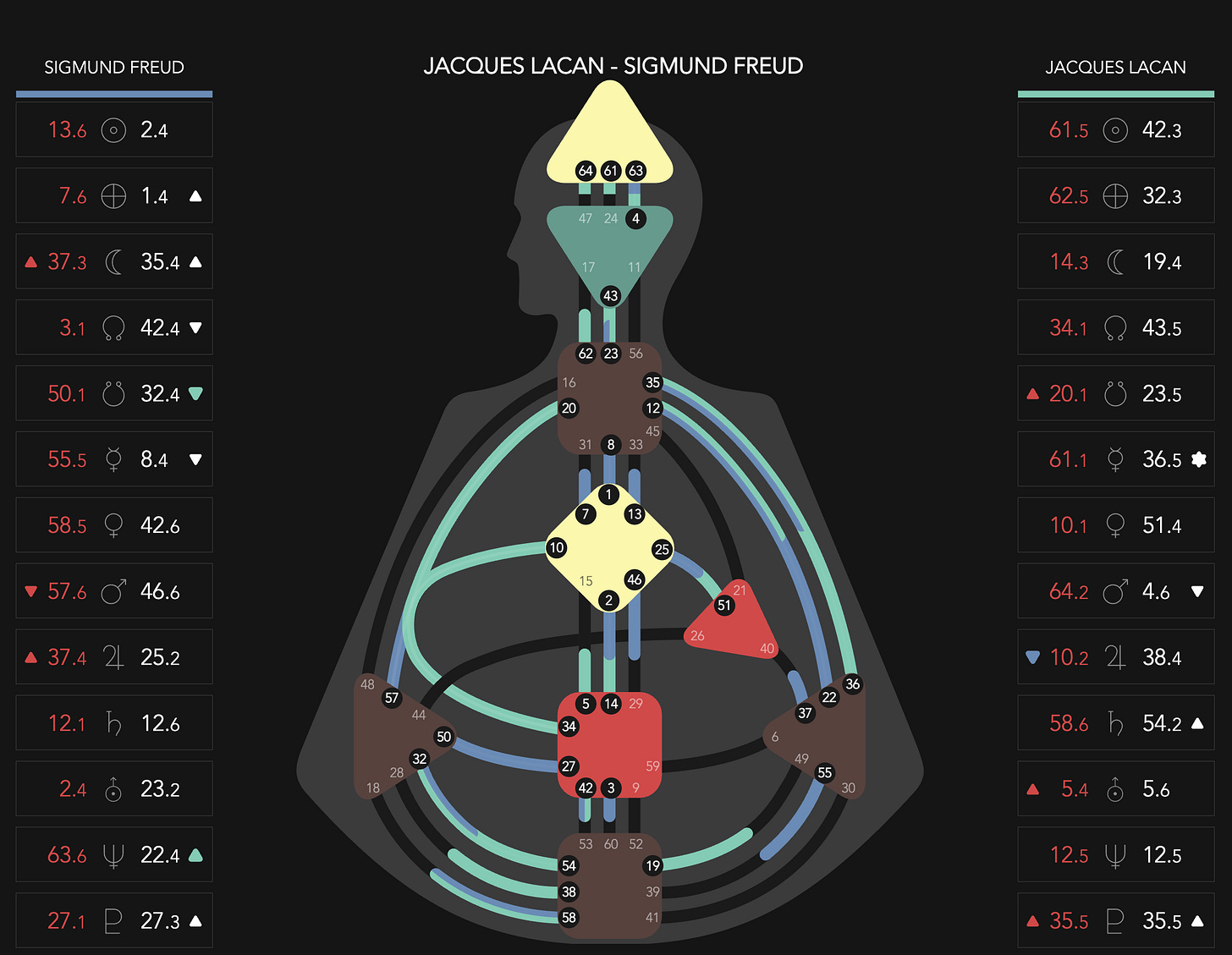

Birth Data and Bodygraph

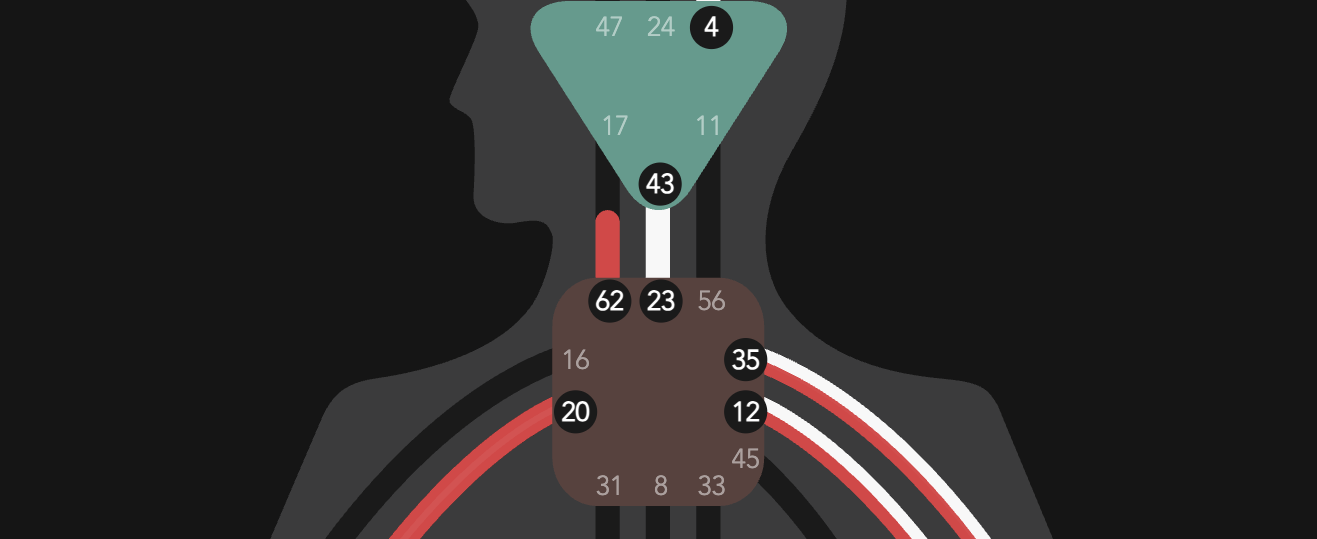

Lacan was born on April 13, 1901, at 14:30 in Paris, France. His birth time is sourced from a birth record collected by the Swiss-French psychologist, Françoise Gauquelin. Based on this data, we observe the following in Lacan’s bodygraph:

Lacan is a 3/5 Manifesting Generator, with an Emotional Authority, born on the Right Angle Cross of Maya.

Seven centers are defined: (Ajna, Throat, G, Sacral, Spleen, Solar Plexus, Root), and two centers are undefined (Head, Heart). No centers are completely open.

Six channels are defined:

Transformation (54-32)

Structuring (43-23)

Transitoriness (35-36)

Charisma (20-34)

Exploration (10-34)

Awakening (20-10).

The 5th line predominates with 9 activations, followed by the 4th and 1st lines with 4 activations each.

The Knowing/Individual circuit predominates with 9 activations, followed by the Sensing and Understanding circuits with 5 activations each.

You know that “martyr” means witness—of a more or less pure suffering.

—Jacques Lacan, Seminar XX

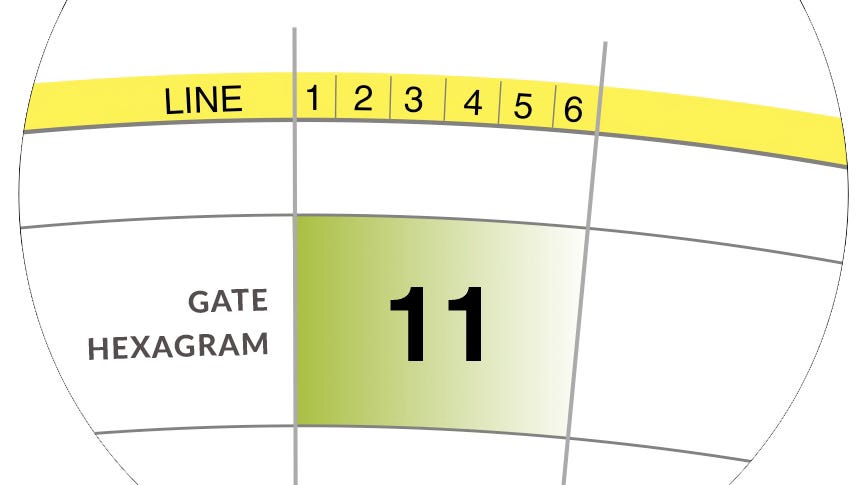

I. Lacan as Martyr/Heretic

As a system, Human Design synthesizes the sixty-four hexagrams with the twelve signs of the astrological zodiac. The zodiacal placements of the astrological birth chart are thus rendered in hexagrammic correspondence. The hexagrams constitute “gates” in centers that connect to other centers through the formation of a channel. Following the structure of the Yijing, each hexagrammic gate is read in six possible lines, shown in the decimal points after each gate. The profile is determined by reading the line numbers associated with the Sun placement in the design and personality placements. In Lacan’s design, the personality Sun is placed in gate 42 and operates on the 3rd line (42.3); the design Sun is placed in gate 61 and operates on the 5th line (61.5). Therefore, Lacan’s is a 3/5 profile.

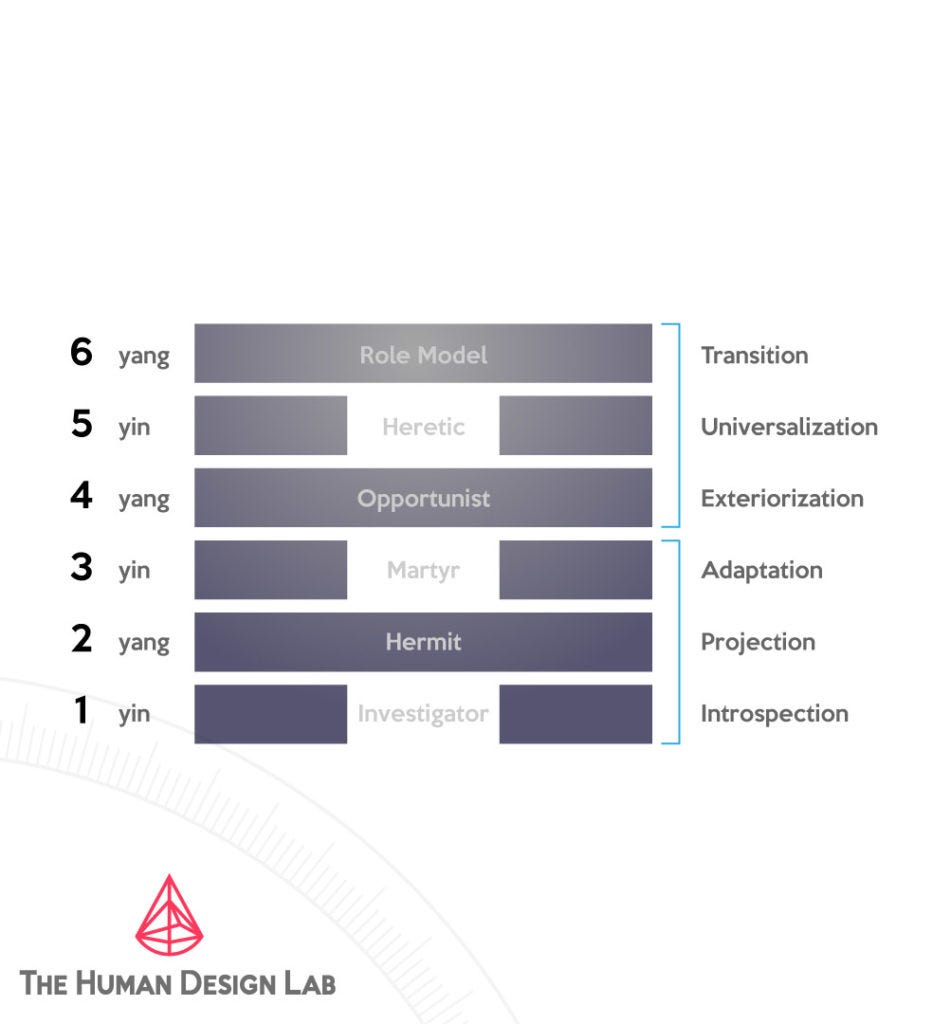

The profile is the hexagrammic foundation of the design.2 The first number represents the conscious aspect (or “personality”) and the second number represents the unconscious aspect (or “design”). The six lines function as primary roles in the person’s design, giving each gate 6 possible roles and rendering twelve possible profiles. Each line functions as a signifier described with a single word. The 3rd line is the “Martyr” and the 5th line is the “Heretic”. Therefore, a 3/5 profile is described as the duality of the Martyr/Heretic.

Lacan is an archetypal example of the Martyr/Heretic. In 1953, Lacan was expelled from the Société Parisienne de Psychanalyse (SPP) due to disagreements regarding the length of analytic sessions. Lacan practiced and advocated for a “variable-length” session, which the psychoanalytic orthodoxy rejected in favor of the established “fifty-minute hour”.3 Later that year, Lacan co-founded the Société Française de Psychanalyse (SFP).

In 1963, the International Psychoanalytic Association (IPA) effectively expelled Lacan from its association by requiring the SFP to remove his name from its list of analysts. The SFP’s compliance with this request led to Lacan’s barring from yet another psychoanalytic association, while also stripping him of his authority to train analysts.

In order to continue his work, he founded the École Freudienne de Paris (EFP) in 1964, an association he dissolved a year before his death, with the famous statement, “It is up to you to be Lacanians if you wish. I am Freudian”.

In 1966, Lacan published a collection of his writings titled Écrits, which sold five thousand copies within two weeks of publication. Lacan’s work received significant acclaim and criticism. Roudinesco recounts a notable statement made by Lacan’s former analysand, Didier Anzieu, who called him “a heretic” and predicted “his downfall”.4

With this rather brief excursion into Lacan’s work, we are given a glimpse of Lacan’s style in the manner of the Martyr/Heretic. He was martyred by the psychoanalytic establishment of his time, excluded from the professional body of psychoanalysts, and proclaimed as a heretic. The process of the 3rd line involves “making and breaking bonds”, a theme we see throughout Lacan’s professional and personal life. Lacan’s expulsion from the orthodoxy forced him to embrace his own context and elaboration, which he did with great success. By the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s, Lacan’s seminars were attracting nearly a thousand attendees, becoming an epicenter of French intellectual life. Therefore, by embracing his style, Lacan moved into the personal destiny laid bare before him.

Of the six lines, it is the 5th line that appears to operate purely on the mechanism of unconscious processes. Ra describes the 5th line as a seduction and projection field, where others project what they need and think a 5th line person can provide them with.5 “If a practical solution is not provided, if what you have given them is a ‘house of cards’, your reputation suffers and the ‘heretic will be burned at the stake’”.6 It is not too adventurous to propose that Lacan’s experience of the 5th line led to one of his most pivotal articulations: “Desire is desire of the Other”. The 5th line person functions as an object-cause of the Other’s desire via the mechanics of a transferential field.

Since the 5th line is unconscious in Lacan’s design, it is a process he became aware of over time. As we saw, Lacan initially endeavored to work in the context of the psychoanalytic establishment of the time, even characterizing his thought in relation to its founder. However, Lacan’s teaching could not be farther from the notion of “traditional” or “orthodox”. We can see Lacan becoming conscious of this fact in various ways, but a notable example is given in his one and only televised discourse. In one part of the partly-improvised discourse, Lacan gives one of his best definitions of analytic discourse:

What I call the analytic discourse is the social bond determined by the practice of an analysis. It derives its value from its being placed amongst the most fundamental of the bonds which remain viable for us.7

What does Lacan mean by a “social bond”? “Social” comes from the Latin socialis, meaning “allied”, the root of which is socius, meaning “friend”. Lacan is thus invoking “social” in the sense of true friendship, a connection that encounters the real through a collective ethic of practice.

After hearing this remark, Lacan’s student and future heir, Jacques-Alain Miller, then asks, “But you yourself are excluded from that which makes for social bonds between analysts, aren’t you?”—to which Lacan responds:

The Association, so-called “International” (although that is a bit of a fiction) having been for so long limited to a family business—I still knew it in the hands of Freud’s direct and adopted descendants, if I dared. But I warn you that here I am both judge and plaintiff, hence partisan. I would say that, at present, it is a professional insurance plan against analytic discourse. The PIPAAD.8 Damned PIPAAD!

They want to know nothing of the discourse that determines them. But they are not thereby excluded from it; far from it, since they function as analysts, which means that there are people who analyze themselves by means of them.

So they satisfy this discourse, even if some of its effects go unrecognized by them. On the whole, they don’t lack prudence; and even if it isn’t the true kind, it might be the do-good kind. Besides, they are the ones at risk.

The transcript of the discourse was eventually published as Television: A Challenge to the Psychoanalytic Establishment, where the subtitle alone establishes Lacan’s now-conscious heresy.

In Seminar VIII, Lacan provides an exegesis of his notion of transference through a commentary on Socrates. In one such example, Lacan writes:

[Alcibiades] attempted to seduce Socrates, he wanted to make him, and in the most openly avowed way possible, into someone instrumental and subordinate to what? To the object of Alcibiades’ desire—ágalma, the good object.

I would go even further. How can we analysts fail to recognize what is involved? He says quite clearly: Socrates has the good object in his stomach. Here Socrates is nothing but the envelope in which the object of desire is found.

It is in order to clearly emphasize that he is nothing but this envelope that Alcibiades tries to show that Socrates is desire’s serf in his relations with Alcibiades, that Socrates is enslaved to Alcibiades by his desire. Although Alcibiades was aware that Socrates desired him, he wanted to see Socrates’ desire manifest itself in a sign, in order to know that the other—the object, ágalma—was at his mercy.

Now, it is precisely because he failed in this undertaking that Alcibiades disgraces himself, and makes of his confession something that is so affectively laden. The daemon of Αἰδώς (Aidós), Shame, about which I spoke to you before in this context, is what intervenes here. This is what is violated here. The most shocking secret is unveiled before everyone; the ultimate mainspring of desire, which in love relations must always be more or less dissimulated, is revealed—its aim is the fall of the Other, A, into the other, a.910

Socrates was proclaimed a heretic and sentenced to death. By drinking the poison that would kill him without hesitation, Socrates established himself as a martyr. In the person of Socrates, we are given an archetypal example of the martyr/heretic dyad. Why did Lacan speak of Socrates in order to illustrate transference? Because the 5th line is the phenomenology of transference, which a martyr/heretic knows well.

II. Lacan as Genius-Freak

Rather than analyzing all of Lacan’s defined channels, I wish to focus on the channel which, in my view, bears Lacan’s signature: the Channel of Structuring (43-23). The Channel of Structuring is formed by the connection between hexagram 43, “Breakthrough—The Gate of Insight”, and hexagram 23, “Splitting Apart—The Gate of Assimilation”.11 In the bodygraph, hexagram 43 is placed in the Ajna center, and hexagram 23 is placed in the Throat center.

The Ajna center conceptualizes original insights while the Throat center manifests them in speech. When the Ajna is connected to the Throat, an individual is given the ability to articulate and manifest their unique insights. Of the three channels that connect the Ajna to the Throat, the 43-23 is especially striking. It is named “the channel of structuring” because it gives the ability to structure one’s insights in speech, where “speech” encompasses spoken and written forms of expression.

The defining influence of this channel is exemplified in Lacan’s most fundamental dictum: “The unconscious is structured like a language”. Even a cursory reading of Lacan reveals the profound influence of structuralism on his interpretation of psychoanalysis.

The channel of structuring is described as “a design of individuality (from genius to freak)”. Lacan’s expulsion from the psychoanalytic establishment serves to highlight his individuality—from the founding of his own school to the articulation of an original pedagogy of psychoanalysis. Ra describes the trajectory of this channel as “genius to freak” to indicate that the articulations of an individual with this channel are either recognized (“genius”) or seen as preposterous (“freak”). We see this phenomenon so clearly in the history and process of Lacan’s work.

Lacan is commonly accused of being an obscurantist—intentionally concealing the meaning and implications of his words. To this point, I recently met a Jungian analyst and introduced myself as a Lacanian analyst, to which he responded, “Lacan! He’s so confusing!”.12

The channel of structuring is considered a “projected” channel, which means that it must be recognized in order for its energy to manifest.13 This means that the insights and expressions of the 43-23 must develop a sense of timing, knowing where and when to speak their distinctive discourse.

In Lacan’s design, the 43-23 is a conscious channel formed by astrological placements based on his birth date, rather than on the “design” date, which is calculated 88 degrees (or roughly 88 days) before the birth date.14 The idea is that the birth date forms the natal personality (which is conscious) and the design date forms the pre-natal design (which is unconscious). Since Lacan’s Channel of Structuring is conscious, it forms and functions in and as his personality. This channel can be formed by any planetary placements, but in Lacan’s case, it is formed by his north and south nodes, giving the 43-23 an evolutionary connotation. For Lacan, gates 43 and 23 are also associated with the 5th line, which illustrates the heretical structure of his teaching.

The definition of the 43-23 as a movement between genius and freak explains why opinions are fervently divided on the value of Lacan’s teaching. Lacan does not have a universal value—his expression is for those who recognize the original contours of his speech. For the rest, his genius is a freakish semblance that splits apart all attempts at assimilation.

III. Lacan as Teacher: The Right Angle Cross of Maya

In Human Design, the concept of the Incarnation Cross signifies an individual's purpose. The cross is comprised of the four gates corresponding to the Sun and Earth positions in the personality and design. Each cross is augmented by its position within one of four possible “quarters” of the human design mandala (initiation, civilization, duality, or mutation) and is further defined by its “angle” (left or right).

Lacan was born on the Right Angle Cross of Maya (42/32 | 61/62) in the first quarter of initiation.15 The Right Angle Cross of Maya is categorized under Gate 42—Increase. Ra describes individuals born on the Right Angle Cross of Maya as “[t]rend setters grounded in properly evaluated detail who promote growth by bringing one cycle to completion, thus setting the stage for inspired new beginnings”.16 Lacan was one such pioneering spirit who brought psychoanalysis into new contexts of understanding while retaining its original essence. In this sense, Lacan was a true innovator.

And what of maya? The descriptor, māyā, is of Sanskrit origin and means “measure”, “unreal appearance”, “veil”, and “phantom”. In the context of Indian philosophy, māyā signifies the illusory nature of all conditional phenomena. Māyā is a deceptive appearance, or what Lacan calls the “grimace of the real”. Thus, to live in a conditional world is to traverse a fantasy, a virtualization of the real.

A related meaning of māyā is “fraud” or “deceit”. Perhaps Chomsky’s characterization of Lacan as “charlatan” was, in fact, an incomplete recognition of Lacan’s Incarnation Cross of Maya. It is intriguing that Lacan opens his televised discourse with the following confession:

I always speak the truth. Not the whole truth, because there’s no way to say it all. Saying it all is literally impossible—words fail. Yet, it’s through this very impossibility that the truth holds onto the real.17

A defining characteristic of Lacan’s teaching is his renunciation of ego psychology. In his formulation of the “mirror stage”, Lacan describes the infant’s recognition of its image in a mirror as an imaginary identification. In contrast to his predecessors and contemporaries, Lacan emphasizes the illusory nature of the ego and calls forth a confrontation with the real. Lacan’s use of the phrase “the real” points to a range of influences, from surrealism to modernism to Buddhism. Where psychoanalysis had previously endeavored to strengthen the ego-construct as essential to psychological well-being, Lacan unveils the real.

The body of Lacan’s spoken and written work constitutes a teaching, rather than a mere philosophy. The term “teaching” is derived from the Old English tæcan, meaning “show, present, point out”. The etymology is traced to an Indo-European root shared in Greek, deiknunai, meaning “show”, and deigma, meaning “sample”. Lacan uses language to point out the structure of the unconscious. The apparent difficulty of his communication is not due to intentional obscurity but reflects the cipher that is the unconscious itself.

In his final seminar, Encore, Lacan comments on the function of his Écrits:

It is rather well-known that those Écrits cannot be read easily. I can make a little autobiographical admission—that is exactly what I thought. I thought, perhaps it goes that far, I thought they were not meant to be read.

. . . This writing (écriture) stemmed from an initial reminder, namely, that analytic discourse is a new kind of relation based only on what functions as speech, in something one may define as a field.18

Lacan is situating his written work as “analytic discourse”, a textual mode of communication that is transparent to the field and function of the unconscious. As Grigg writes:

Lacan is a stylist, a baroque and defiant one to be sure, but one with, as Malcolm Bowie has pointed out, a capacity for formulating theses that are pithy and memorably simple . . . [T]hey indicate the presence of a didactic side in Lacan’s work, one that merits the term ‘teaching’.19

One reads Lacan as one reads a scriptural text whose letter speaks to the agency of the unconscious to make an instance of the real.

IV. Returning to Freud: Connection Themes

Lacan describes his project as a “return to Freud”, but he also speaks before and after Freud. We must ask, what exactly is the connection between Lacan and Freud? We venture an answer by examining the connection themes between their human designs.

Lacan and Freud were both Manifesting Generators, a variation on the Generator type. In Human Design, “types” describe modes of being.20 As the name implies, a “Generator” functions with an “open and enveloping aura” as a creative force in the world. The signature of the Generator type is the defined Sacral center, described as a fertile power of creativity and sexuality. A Manifesting Generator is further defined by a motor-to-Throat connection.21

In Lacan’s design, the Solar Plexus motor is connected to the Throat via the Channel of Transitoriness (35-36), and the Sacral motor is connected to the Throat via the Channel of Charisma (20-34). In Freud’s design, the Solar Plexus motor is connected to the Throat via the Channel of Openness (12-22).

When Lacan and Freud’s designs are layered upon each other, all nine centers are defined, forming a complete connection.22 This theme is further examined via four possible categories of connection between the nine centers: electromagnetic, compromise, companionship, and dominance channels.23

Electromagnetic Channels: Where Two Ends Meet

Lacan and Freud’s connection forms six electromagnetic channels:

Beat (2-14)

Initiation (51-25)

Power (34-57)

Perfected Form (10-57)

The Brain Wave (57-20)

Logic (63-4).

This is a significant number of connections that reveals the “spark” between them. Through these six channels, we can see the specific ways in which Lacan and Freud complement each other.

In addition, there are four compromise channels, five dominance channels, and no companionship channels.

Compromised Channels: A Conflictual Dynamic

Freud is compromised by three of Lacan’s channels:

Transitoriness (35-36)

Transformation (54-32)

Structuring (43-23)

Lacan is only compromised by one of Freud’s channels:

Openness (12-22).

Dominance Channels: Experiencing the Other

While compromised channels suggests potential conflict, dominance channels allow a person to be experienced as they are, outside of the connection. In the cloistered context of the 9-0 connection, dominance provides an outlet. Freud is dominated by three of Lacan’s channels:

Charisma (20-34)

Exploration (10-34)

Awakening (20-10)

While Lacan is dominated by two of Freud’s channels:

Inspiration (8-1)

Preservation (27-50)

Freud and Jung: Connections and Splits

For context, we can note that Freud and Jung’s connection theme is a 7-2 (“work to do”) with four electromagnetic channels, four compromise channels, and three dominance channels. Their four electromagnetic channels are:

Transitoriness (35-36)

Initiation (51-25)

The Prodigal (33-13)

Emoting (39-55)

In terms of compromise, Jung compromises Freud with three channels:

Maturation (34-52)

The Alpha (31-7)

Perfected Form (10-57)

Freud compromises Jung with:

Preservation (27-50).

In terms of dominance, it is Freud who dominates Jung with two channels:

Inspiration (8-1)

Openness (12-22),

while Jung dominates Freud with one channel:

Recognition (30-41).

Lastly, we can note that the Freud-Lacan and Freud-Jung connections share the electromagnetic Channel of Initiation (51-25). A full analysis of the channel connections between Lacan and Freud (and Freud and Jung) is a worthy exploration that I only note for now.

In addition to their type resonance, Lacan and Freud have compatible profiles. Human design views sequential profiles as being compatible. Lacan is a 3/5 profile and Freud is a 4/6 profile, placing them in a compatible sequence to each other. However, in this sequence, Lacan precedes Freud, signifying the nature of his “return” as a prophecy.

V. Lacan as Prophet: The Future of Psychoanalysis

The term “prophet” comes from the Greek prophētēs, meaning “interpreter, expounder”. Examined at its root, pro means “before” and phētēs means “speaker”. Therefore, a prophet is “one who speaks before”. In a discourse titled “Guru As Prophet”, Adi Da explores the prophetic function of the spiritual teacher:

In the world, generally, [the Guru] must serve the crisis of understanding, which confounds the search, all need for consolation, fascination, all need for cultural and cultic games. In the world he may function, if he appears at all, in the role of the prophet, which is essentially an aggravation, a criticism, an undermining of the usual life.24

Adi Da views the public function of a teacher as “prophet and critic”. Clarifying his usage, Adi Da notes that the true meaning of prophet is not a psychic function of foretelling the future, but a critical function that undermines the egoic mechanism:

When I speak of the function of the man of understanding as prophet, it is in that sense, as critic, not as someone who exercises secondary psychic powers to foretell the future.

. . . The true prophet doesn’t lead a person to align himself with karmic destiny. He leads him always toward a radical new position relative to the whole force of his ordinary life.25

In the opening remarks of Television, Lacan indirectly speaks to his role as prophet:

. . . There is no difference between television and the public before whom I’ve spoken for a long time now, a public known at my seminar. A single gaze in both cases: a gaze to which, in neither case, do I address myself, but in the name of which I speak.

Do not, however, get the idea that I address everyone at large. I am speaking to those who are savvy, to the nonidiots, to the supposed analysts.26

Lacan’s seminars were famously open to the public and became a center of Parisian intellectual life. In this sense, Lacan maintained the paradoxical gaze of the prophet: at once looking at the public while speaking in private. Therefore, the prophetic gaze also stands at the juncture of the public and the private, the exoteric and the esoteric, the universal and the personal.

Prophet as critic is prophet as heretic, and thus prophet as martyr. Lacan functions as a prophet because his return to Freud uncovers a prior truth that feeds the future of psychoanalysis. By undermining the egoic strictures that contain the unconscious, Lacan points to the structure that speaks behind thought, a sound waiting to be heard in the real.

See David Macey’s Lacan in Contexts. London: Verso, 1988.

The founder of the system, Ra Uru Hu, describes the profile as the “costume” one wears in life. See Bunnell and Hu (2011).

An excellent discussion of Lacan’s variable-length session is found in Stuart Schneiderman’s Jacques Lacan: The Death of an Intellectual Hero. Boston: Harvard University Press, 1983. Lacan discusses the topic himself in “The Field and Function of Speech and Language” in Écrits. Translated by Bruce Fink. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2006.

Roudinesco, Elisabeth. Jacques Lacan: An Outline of a Life and History of a System of Thought (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), 328.

Ra says that the “hopes and dreams of humanity rest on the shoulders of a 5th line” person. Bunnell, Linda and Hu, Ra Uru. The Definitive Book of Human Design: The Science of Differentiation (Carlsbad, CA: HDC Publishing, 2011), 279.

Ibid.

Lacan, Jacques. Television: A Challenge to the Psychoanalytic Establishment (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1990), 14.

“PIPAAD” is Lacan’s critical acronym for the IPA: “Professional Insurance Plan Against Analytic Discourse”.

Lacan, Jacques. Transference: The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book VIII. Edited by Jacques-Alain Miller. Translated by Bruce Fink. (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2015), 176.

In Lacan’s teaching, “object a” refers to the object-cause of an unattainable desire, and the capital “A” refers to the Other.

In astrological terms, gates 23 and 43 correspond to the Taurus/Scorpio axis, respectively.

Even Chomsky, with his universal grammar, struggled to recognize Lacan, declaring him a “charlatan” after attending one of his seminars.

There are four types of channels in the bodygraph: projected, manifested, generated, and manifested generated. A projected channel has no connection to the Sacral center and therefore operates on the basis of an invitation.

The design date is calculated by subtracting 88 degrees of a solar arc from the birth calculation. This calculation is posited as the pre-natal constitution of the individual. When the design chart and birth chart are combined, they form the bodygraph that is typically analyzed in Human Design readings. However, these two aspects of the individual can also be analyzed independently and as a dynamic interaction.

As with many aspects of the Human Design system, no explanation is given for this calculation. This ambiguity is rationalized by asserting the prophetic and revelatory epistemology of Human Design. In other words, it is not known how we know what we know, except that it was spoken to us.

Ra describes the theme of the quarter of initiation as a “purpose fulfilled through mind, through thinking, educating, conceptualizing, explaining and sharing what it means to be alive in a Form”. (2011, 290). The right angle indicates a personal destiny in contrast to the transpersonal destiny of the left angle.

Ibid., 297.

Lacan (1990), 3. The punctuation of this translated passage has been adjusted for clarity.

Lacan, Jacques. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book XX: Encore 1972-1973. Edited by Jacques-Alain Miller. Translated by Bruce Fink. (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1998), 26-27.

Grigg, Russell. “Englishing Lacan.” Meanjin, December 11, 2005. https://meanjin.com.au/essays/englishing-lacan/

There are five possible types: Generator, Manifesting Generator, Projector, Manifestor, and Reflector.

Four of the nine centers are considered motor centers: Sacral, Solar Plexus, Root, and Heart.

Ra describes this connection theme with the rhyming phrase “9-0 / nowhere to go”.

Electromagnetic connections are formed when the two charts form a new channel that neither design contains in itself. This can only happen when each design has a gate that mirrors the other, forming a complete channel that is otherwise partial in each individual. The electromagnetic connection is thus a natural and mutual attraction.

Compromised connections are formed when one individual has a complete channel that is partial in the other. The person with the partial channel is thus “compromised”.

Companionship connections are formed when both individuals share a complete channel, creating a mutuality.

Dominance connections are formed when an individual has a complete channel that the other does not have at all.

Jones, Franklin [Adi Da Samraj]. The Method of the Siddhas (Middletown, CA: Dawn Horse Press, 1973).

Ibid.

Lacan (1990), 3.

References

Bunnell, Linda and Hu, Ra Uru. The Definitive Book of Human Design: The Science of Differentiation (Carlsbad, CA: HDC Publishing, 2011).

Grigg, Russell. “Englishing Lacan.” Meanjin, December 11, 2005. https://meanjin.com.au/essays/englishing-lacan/

Jones, Franklin [Adi Da Samraj]. The Method of the Siddhas (Middletown, CA: Dawn Horse Press, 1973).

Lacan, Jacques. Television: A Challenge to the Psychoanalytic Establishment (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1990).

Lacan, Jacques. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: On Feminine Sexuality, The Limits of Love and Knowledge, Book XX: Encore 1972-1973. Edited by Jacques-Alain Miller. Translated by Bruce Fink. (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1998).

Lacan, Jacques. Transference: The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book VIII. Edited by Jacques-Alain Miller. Translated by Bruce Fink. (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2015).

Roudinesco, Elisabeth. Jacques Lacan: An Outline of a Life and History of a System of Thought (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999).

Macey, David. Lacan in Contexts (London: Verso, 1988).

Shneiderman, Stuart. Jacques Lacan: The Death of an Intellectual Hero. (Boston: Harvard University Press, 1983).